日志

The US-China trade war: can Trump learn from history and resolve it?

|

The US-China trade war: can Trump learn from history and resolve it?

China’s inexorable rise has seen an inconsequential trade gap with the US balloon into a multitrillion-dollar chasm. But how and why did it happen, and can it be settled?

In a look back at conflicts that have demanded the attention of political and business leaders over the past half-century, one stands out for its intractability: the long-running trade war between the United States and China – an ongoing series of skirmishes and battles over US access to Chinese markets and China’s access to American technology. Hot wars, cold wars, culture wars and 10 Star Wars films have come and gone, while trade warfare has raged on.

Sino-American friendship and trade dates back two centuries, reaching an apogee of sorts when the countries fought side by side in the second world war, an alliance that ended with the 1949 Communist victory in China’s civil war. The following year, a million People’s Liberation Army (PLA) “volunteers” streaming across the Yalu River into North Korea to fight United Nations troops triggered a 21-year US trade embargo.

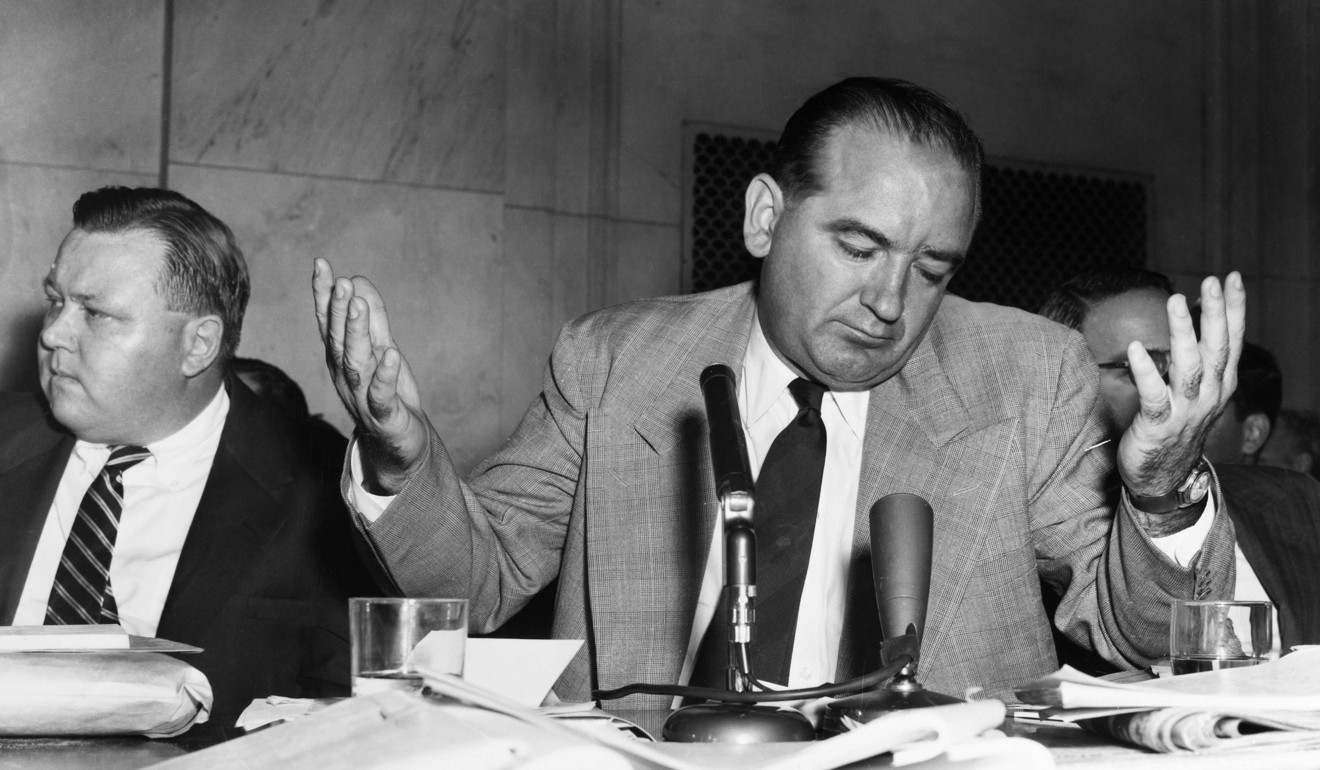

“Who lost China?” was a question that brought on widespread recriminations in post-war Washington, added fuel to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hunt for communists in the government and helped a young congressman from California, Richard Nixon, rise to prominence as one of America’s leading anti-communists.

By the time the two sides resumed relations, in the early 1970s, the US and the Soviet Union were superpower adversaries in a two-way race for the military supremacy that advanced technology conferred. “Communist China”, as it was officially known in the US, was one of the poorest nations on Earth.

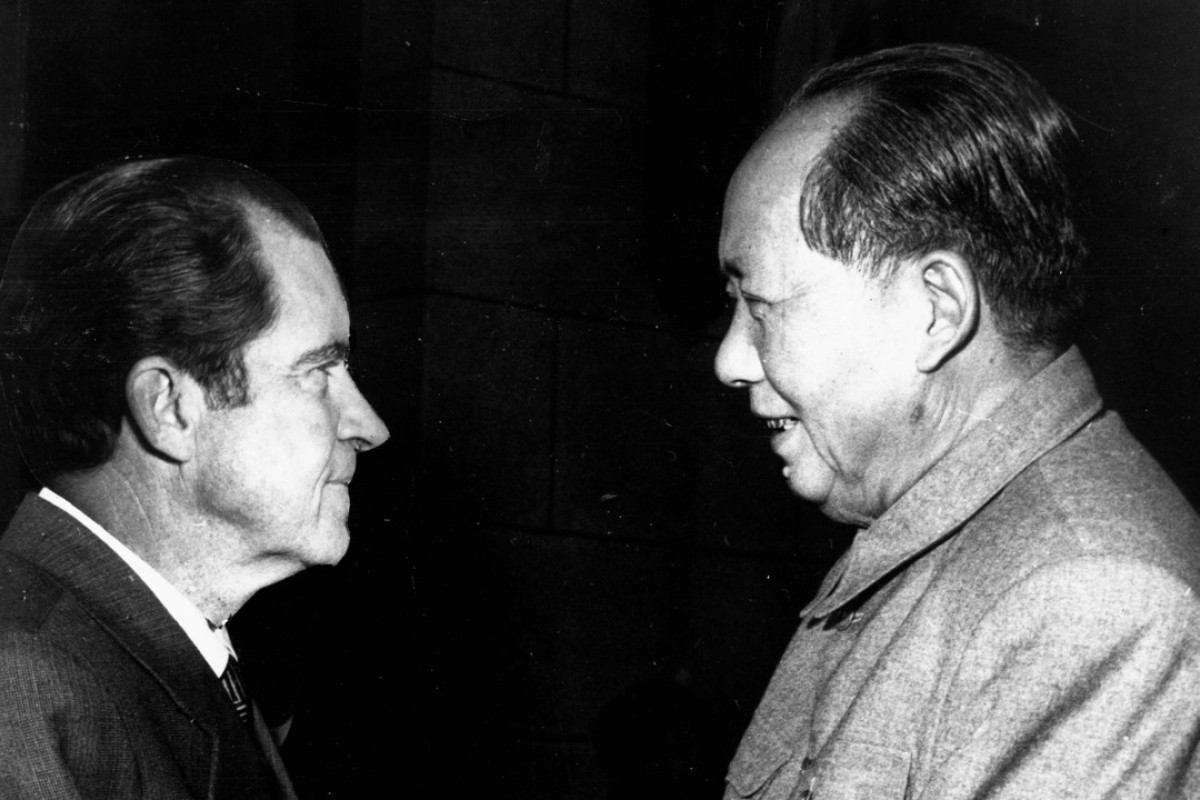

After two decades of isolation and internal ructions, and looking at a Soviet military build-up along its northern border, where the two sides had clashed in 1969, China’s leaders knew they needed technology to modernise their military and economy. But they waged fierce internal battles about whether and how to interact with the “American imperialists and their running dogs”, the title of an English-language propaganda bulletin found in national security adviser Henry Kissinger’s Diaoyutai State Guesthouse room when he visited Premier Zhou Enlai in 1971, to pave the way for Nixon’s visit to Zhou and Mao Zedong the following February.

Though trade was not discussed much during Nixon’s visit, officials had already begun discussions about which technologies the US would share. Much of America’s “advanced technology”, developed by Fortune 500 companies, was “dual use” – it had military as well as civilian applications. Washington restricted its sale, corporate commercial applications notwithstanding. A common Beijing complaint about such restrictions was that the US was treating China as it treated the Soviets – and were not the Soviets their common enemy?

Why Trump’s China trade war could also hurt US allies

In 1970, China’s per capita gross domestic product was about US$113. The country had the bomb, a massive military – and a heavily agrarian, 19th-century economy. The release in the early 2000s of previously classified US State Department documents of the period showed little concern from Nixon or Kissinger about economic competition from China. Military competition from the USSR was the threat of the day and the driver of rapprochement.

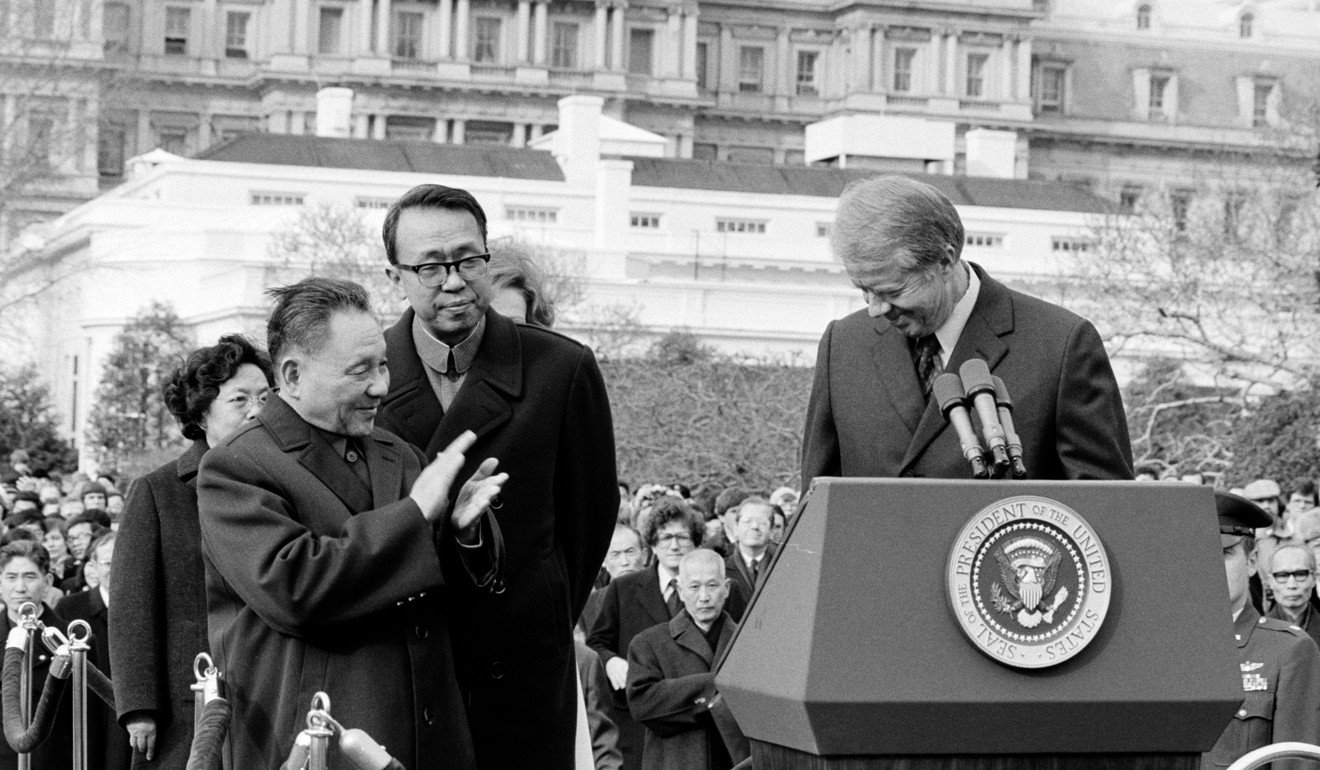

Nixon, the rest of his presidency soon bogged down by Watergate, never completed what he called “normalisation”. Seven years would pass before Jimmy Carter sealed the deal with Deng Xiaoping in December 1978. Within weeks, Deng, his wife and a small delegation were in the US, charming Americans, dining at a lavish White House dinner, travelling the country – and seeing first-hand what three decades of isolation had deprived them of.

Normalisation would be Deng’s road to US technology, and while he drove it fast, the road would prove bumpy. China had hardline opponents to relations with the West and Deng fought internal battles over the issue for two decades. A Deng biographer, Harvard University’s Ezra Vogel, recounted a 1975 argument about cargo ships with Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing.

Sour-faced Jiang, who sat next to Nixon at a Chinese opera performance during his 1972 visit, was anti-US to the core. Deng, after becoming vice-premier in 1975, the year before Zhou and Mao died, and eager to increase trade, supported China’s purchase of large, foreign-made cargo ships. Jiang, citing the recent construction of a 10,000-tonne Chinese freighter, wrote to Mao and accused Deng of having the mentality of a “comprador” – an agent of a foreign trader. At a Politburo meeting soon afterwards, she called him “a slave to the West”. The usually cool Deng, thrice banished from the leadership, “lost it”, Vogel recounted, replying “angrily” that he had travelled abroad half a century earlier on a ship four times the size of the Chinese ship. Jiang was “out of touch”.

By the time of his US visit in 1979, Deng knew exactly what he wanted. After diplomatic niceties and discussions with Carter in Washington, he went to Atlanta, to tour a modern Ford plant; to Houston, to visit Nasa and a manufacturer of the latest oil-drilling technology; and to Seattle, to see Boeing’s massive factory.

The US had hardliners, too. Deng’s Texas visit was illustrative of the mixed feelings of Americans. Texas’ senators, a Republican and a Democrat, would not meet him and, although the governor and Houston’s mayor did, a comment by the former was indicative of US ambivalence and knowledge about China. “We will turn out in a normal show of Texas hospitality,” he said. “Whether we agree with him politically, philosophically or whether we like chop suey or not, is beside the point.”

Texas oil men liked chop suey. Some, connected through soon-to-be vice-president George H.W. Bush, had no qualms about selling the latest oil-drilling technology, including offshore, to China, and China needed it. Deng planned to raise much of the foreign currency needed to buy technology and build modern factories by selling oil, much of it to Japan. China was, after all, the ninth largest oil-producing country in the world.

A foreshadowing of trouble appeared on the trip, however. While pressing relentlessly to acquire only the latest technology, Vogel noted that Deng appeared not to grasp “the calculations of private companies in using patents and copyrights to recoup their research and development expenses”. This seems difficult to believe. But if it set off alarm bells about intellectual property protection, they do not seem to have been loud. Close scrutiny would have exposed a harsh reality – no effective legal means existed in China to protect US intellectual property. Businesses going in early knew that, or would find it out soon enough, but they went anyway, setting a precedent of laxity about IP protection that would snowball in the coming decades.

Opinion: How Xi Jinping can rival Deng, with a little help from US

For the communists, their early decades formed in the shadow of Lenin’s and Stalin’s USSR, technology had usually come free of charge. Until Mao and Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, fell out in the 1950s and Soviet scientists went home, the Soviets, recognising the value of 700 million more communists in their world, had openly shared their military technology with their comrades. If the folklore is to be believed, they should have burned, not shredded, their technical nuclear papers when they left, as Chinese scientists meticulously pieced them back together and finished the job.

In 1980, China’s per capita GDP was about US$195. Trade between the two countries was negligible, but Deng, whom the US newspapers were still calling Teng Hsiao-ping, while perhaps not quite understanding patent and copyright laws, understood marketing. “Teng Speaks of Plans For Imports in Billions”, read a New York Timesheadline on the last day of his 1979 trip.

Chinese students were soon flocking to US universities. A 1983 Timesarticle noted that “the subtler aspects of technology transfer that [were] going vigorously forward, to the long-term benefit of China’s development plans […] included 10,000 students, most pursuing science and engineering programs”.

Many of the Chinese students of the 80s and 90s returned to become the deans and professors of the coming decades, passing along their knowledge and nurturing its proliferation in China’s universities, some of which have joined the ranks of the world’s elite.

Ronald Reagan, an unreformed foe of communism, campaigning in part on a promise to overturn normalisation, defeated Carter in the November 1980 US presidential election. Once in office, though, like his predecessors, he focused his animus on the Soviets, who had invaded Afghanistan, and whom he was determined to put out of business. Reagan began a decade-long economic war – the “arms race” – that eventually accomplished just that. The dissolution of the USSR, in 1991, started a subsequent decade-long celebration in the West, with one historian writing fatuously about the “end of history” – democratic capitalism had conquered totalitarian communism. It was clear, and it was inexorable.

Though Deng was not credited until after the Tiananmen Square crackdown on students in 1989 with his famous 24-character strategy, which included a caution to fellow leaders to “maintain a low profile”, China mostly did just that during the Reagan years. Trade between the two increased steadily, but while facing down the Soviets militarily, the primary economic focus of the US was on its lopsided trade with world-beating, mercantilist Japan. China, like other countries in East and Southeast Asia, was mostly just an interesting place with a lot of potential.

But the advent of digitisation in the 80s did alert the US public to Chinese industriousness in pilfering intellectual property. Software, music and movies all became susceptible to piracy on a scale never before seen. And while those industries were soon calling out China for its leading role in the problem, a discussion about piracy – in a class on managing in developing countries that I took in business school in 1988 – provided some prescience. After several earnest American students expressed ethical outrage about the practice, our professor called on an unusually outspoken student from Japan. I don’t recall precisely everything he said, as he wagged his finger at the class, but it included a reference to China’s per capita income, the retail price of a single copy of Lotus 1-2-3 or WordPerfect, and the word “naive”, which he wasn’t using to describe the Chinese. Americans who expected people who were that poor to pay for software they could get for free were kidding themselves.

China to strengthen crackdown on fake goods, online piracy, says minister

While the US focused on the USSR and Japan, China’s leadership team of the 90s was coming together. Deng spent considerable time discussing the national economy with Jiang Zemin, Li Peng and Zhu Rongji, among others, in the late 80s. The government had opened about a dozen coastal cities and their success as economic drivers was obvious. China was experimenting with capitalism, though mostly avoiding the term.

Many Chinese were also interested in whether their country might open up politically, which led to Tiananmen Square, where any such hopes would come to an abrupt end.

In early March 1990, Harvard’s Vogel wrote that Deng had asked Jiang and Li, unrhetorically, “Why do the people support us?” Answering his own question, he pointed to the economic growth they had been delivering. But Tiananmen had brought down global opprobrium. The Soviet bloc was already in upheaval and their very legitimacy as China’s leaders was now coming down to the economy. He asked what would happen if China’s growth slowed, then answered himself again: “This would be not only an economic problem but also a political one.”

When the Soviet Union finally collapsed the next year, discrediting Marx, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and a political ideology that had lasted just seven decades, China’s leaders knew that there but for the grace of the economy went they.

In 1990, China’s per capita GDP was about US$318. That year, China’s imports from the US were US$4.8 billion – Deng had been keeping his word. Since 1985, China had imported at least US$3.1 billion in goods annually from the US. US imports from China, however, in 1990 were US$15.2 billion.

By 1992, the piracy problem had spurred US officials into action. The US and China signed two memoranda of understanding that year, one regarding market access, another on protection of intellectual property. The first included promises from Beijing to address the trade imbalance, which had grown noticeable. The second included promises to protect American intellectual property.

Democrat Bill Clinton was elected in November that year. In an ironic turnabout of US party roles, he criticised Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, for having gone easy on Beijing in the wake of Tiananmen. No more “coddling dictators”, Clinton had promised, if he was elected.

In the spring of 1993, in his first speech about trade with China, he doubled down. “The core of [Clinton’s trade] policy will be a resolute insistence upon significant progress on human rights in China,” he said. But a year later he flip-flopped and downgraded human rights issues, lumping them into what he called “the full range of US interests”. As a Times opinion writer said, “He caved” having learned “how important the money and other support of major corporations are at election time”.

In early 1995, 2½ years after the 1992 memoranda, the US Government Accounting Office noted that Beijing had “implemented few measures that work toward satisfying [its] provision for enforcement of [intellectual property rights].” The president of the Business Software Alliance industry group testified in a congressional hearing that 94 per cent of packaged software used in mainland China was still pirated.

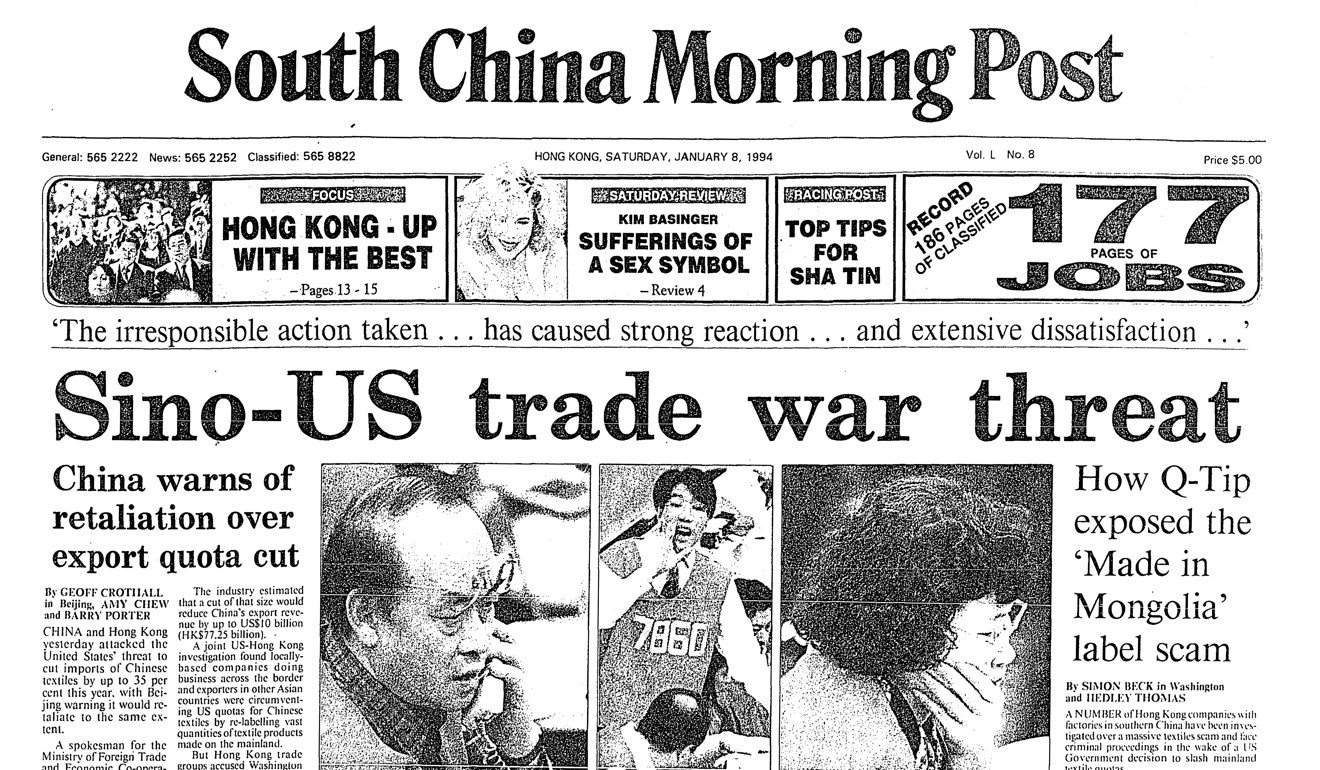

Talk about a “trade war” started to escalate in Washington, with the US threatening to impose punitive tariffs on US$2 billion of Chinese textiles and other goods if Beijing did not fix the problem. Beijing, as today, threatened to retaliate.

On the eve of the deadline for an agreement (mid-June 1996), Clinton’s acting trade representative, Charlene Barshefsky, declared victory. “China agreed to close factories producing pirate CDs, halt exports of pirated goods and open its markets to US film and software,” the Associated Press reported. “American officials will help monitor enforcement.”

But AP also reported scepticism: “Critics charged that China was unlikely to honour [its] pledges.”

A Beijing spokesman claimed that China was advancing its own interests – not giving in to American demands – by launching a crackdown four years after first agreeing to do so. “This by no means indicates that the Chinese side has made a major concession,” he said, presumably with a straight face, at the ministry’s weekly news briefing.

Unenforced IP protection laws in China were not because they could not find the bad guys. The problem was that the bad guys were often the ones making or supposedly enforcing the laws. As The Wall Street Journal noted, “When some of the lawbreakers are members of the nomenklatura or, more daunting still, connected to the People’s Liberation Army, the politics of prosecution become excruciatingly delicate.”

The progression of the 1992 memorandum to protect US intellectual property was an apt microcosm of the relationship. Everyone knew the rules and everyone knew Beijing was not playing by them. Beijing agreed to make changes. The Chinese passed a law. The law did not look like that which was promised. But it really did not matter because it was not enforced anyway.

As the four-year running battle over IP protection wound down to an apparent resolution, the WSJnoted that Beijing had not kept its 1992 market access promises either.

The South China Morning Post headline from 8 January, 1994, highlighting the risk Hong Kong faced as a middleman in US-China trade. Picture: SCMP

The South China Morning Post headline from 8 January, 1994, highlighting the risk Hong Kong faced as a middleman in US-China trade. Picture: SCMP

Over the next three years, despite regular reminders that China might not yet be ready for accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the Clinton administration began a concerted push for exactly that. While, in retrospect, it is tempting to attach little but cynicism to Clinton ignoring the protests of the human rights lobby, the Taiwan lobby, and the anti-communist lobby in general, Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji were making a strong economic case for entry, hitting their stride with economic reform and making painful domestic changes that implied, at some level, a willingness to acknowledge the power of market forces in China’s economy.

Zhu, in particular, was shrewdly using one of America’s most powerful “technologies” to assist in the work: Wall Street’s expertise at restructuring sick, bloated businesses and selling them at a profit. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and others minted billions in fees and profits from minority stakes in Chinese businesses, helping Beijing and China’s chief executives restructure hundreds of state-owned enterprises and list them in initial public offerings that pumped hundreds of billions of dollars from Western investors into China’s economy. Simply having a stock market, which Deng suggested more or less as an experiment, seemed a signal that China wanted in to the WTO.

That China was on the outside in the first place was an accident of history. The predecessor to the WTO, the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (Gatt), was established in 1947 as a way to ensure that the economic chaos that led to the second world war would never be repeated. China, under the Kuomintang, was a founding member, but Mao pulled his communist country out of the capitalists’ club soon after coming to power. Beijing had applied to rejoin under Deng in 1986, unsuccessfully, then tried again, unsuccessfully, when the WTO opened its doors in 1995.

By 1999, Jiang and Zhu were working hard for accession, and a US endorsement – passage of legislation in Congress – was practically (though not technically) a requirement.

And Clinton was aiming to make it the “signature” foreign policy accomplishment of his presidency.

Clinton and his team had to convince Congress to end its annual review of China’s human rights performance – which had been required by federal law since 1974 – and accord China “permanent normal trade relations” with the US. WTO rules would not allow the US to endorse China’s accession if US law left open the annual possibility that the endorsement could be withdrawn.

Clinton had to convince Congress that the deal his team negotiated was good for the US. While American markets had been open to China since the two sides resumed trade in the 70s, China’s markets had many barriers keeping US products out. US negotiators were, in early 1999, trying to finalise an agreement with Beijing that would lower barriers and, finally, protect US intellectual property there.

In April 1999, when it looked as though they were about to reach agreement, Zhu, who had been installed as China’s No 2 in 1999, a few months into the Asian financial crisis, and had done a creditable job stewarding his country through the turmoil, visited the US. His task was sales. He was arguably the first of China’s leaders who seemed even remotely Western. A side-by-side comparison with Jiang underlined that perception. In any assessment of whether the West could do business with China, Zhu would be Beijing’s good cop.

Zhu held a press conference with the president, a first for a Chinese leader in the US. Clinton told reporters that the reforms Zhu was working on “will benefit China and its trading partners, including America’s businesses, workers and farmers”. Moments later he added, “Ultimately, to succeed in the market-based, information-driven world economy, China must continue its efforts toward reform. We disagree, of course, on the meaning and reach of human rights […] I am convinced that greater freedom, debate and openness are vital to improving China’s citizens’ lives, as well as China’s economy.”

The two answered questions for about 90 minutes. At one point, Zhu cracked a joke about accusations the PLA had funnelled US$300,000 into efforts to help Clinton get re-elected in 1996. “Americans really had underestimated us [...] I have US$146 billion of foreign exchange reserves, so I should have put out at least US$10 billion for that purpose. Why just US$300,000? That would be too foolish.”

Reporters who spoke Chinese laughed immediately, and Clinton, standing next to him, the consummate politician, smiled with them. Twenty seconds later, Zhu’s translator hit the punch line. Silence. Lost in translation.

Zhu spent a day in a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, entertaining a succession of chief executives, local politicians and diplomats. Former US ambassador to China James Lilley told The New York Times, “He is selling himself as the intelligent, sophisticated Zhou En-lai guy. He’s post-Tiananmen Square, Shanghai not Beijing, economic reform, free market, MIT and science and all that. All very effective.”

Zhu knew how to press the flesh, but it would be months before the two sides finally reached agreement, in November, the discussions interrupted just weeks after his visit by the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Clinton and his team began selling the deal to Congress. They deployed three talking points, which they repeated incessantly.

First, opening up China would surely bring social and political reform there. Speaking of the power of the internet in early 2000 at the US Coast Guard Academy graduation Clinton predicted confidently, “Last year there were nine million [Chinese connected to the internet]. This year there will be over 20 million. When over 100 million people in China can get on the net, it will be impossible to maintain a closed political and economic society.”

Barshefsky, a lawyer in civilian life, spoke with great certainty about their second talking point: new, even stronger IP protection and enforcement mechanisms that she and her team had extracted in tough negotiations. This time would be different. Testifying before Congress in early 2000, she said the US-China agreement was “fully enforceable” and that China had agreed to “abolish requirements for technology transfer for US companies to export or invest in China.”

Most of all, though, at a time when trade deficits with China looked a lot like trade deficits with Japan, Clinton, his team, and their allies in the House and Senate promised over and over again that China’s accession to the WTO meant Americans should get ready for a massive “one way” flow of economic benefits directly into the US economy.

China was making all the concessions, Clinton promised. The US was making none.

Not everyone bought this, including Clinton’s vice-president, Al Gore, who was running to succeed him in that November’s election and who promised to renegotiate the deal with China to obtain more protections for US workers and for the environment. Many fellow Democrats agreed with Gore. And not a few conservative Republicans, never happy about throwing in with Beijing, opposed the deal on those grounds. Together they formed what the Times called “a bizarre political alliance between conservatives in Congress and labor and environmental groups opposed to the China deal”.

The House of Representatives’ bill, inauspiciously numbered HR4444, passed the House in May 2000 and the Senate in September. Clinton signed the bill into law in October, removing the largest hurdle faced by China in its quest to join the WTO.

At the end of an administration that had battled then claimed victory after victory on IP protection in China, little had actually changed. As the Times reported days before the House vote, “Counterfeiting of computer software and movies on compact discs is now more common than ever.”

In 2000, China’s per capita GDP was about US$959. The US exported US$16.2 billion of goods to China that year and imported US$100 billion. During the 90s, the US imported goods worth US$342.3 billion more than it exported trading with China. And the imbalance was about to take off.

Testifying before Congress in 2010, Robert Lighthizer, who was Ronald Reagan’s deputy US trade representative and is now the US trade representative under president Donald Trump, detailed “what was expected to happen” after Congress approved permanent normal trade relations with China in 2000, “what has actually happened” and “what lessons can be drawn from the experience”.

“US policymakers,” he began, generously, “did not recognise the extent to which China’s economic and political system [was] fundamentally incompatible with our conception of the WTO. [They] significantly misjudged the incentives for Western businesses to shift their operations to China and serve the US market from there, and the US government [was] very passive in response to Chinese mercantilism.”

Once the uncertainty that accompanied the annual normal trade relations review was removed, Lighthizer noted, American companies “shift[ed] production wholesale to China and then ship[ped their products] back to the United States.” The US trade deficit with China ballooned, pumped up by low labour costs made lower by a cheap yuan.

Compounding this offence, in US eyes, and now the subject of a national security action under a US law, the Trade Act of 1974, was the de facto requirement in China that American companies setting up operations there transfer their IP and know-how to Chinese partners.

China promises to retaliate if Trump imposes additional tariffs

The US report on the problem, issued in April by Lighthizer’s USTR office, is technical and legal in nature and includes detailed examples from American companies, who submitted comments during the investigation period. The USTR argues that China’s requirements violate WTO rules but, because the problem is too large and would take too long to resolve through a WTO process, it threatens US national security, hence the US has the right under WTO rules to take unilateral action to protect its interests.

Beijing disputes the US findings. It says US companies that want to do business in China are free to negotiate what technology they transfer and what they chose to hand over was a business decision, freely made.

As if the stakes weren’t already high enough, the White House in June published a policy report titled, “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World”.

In 2010, China’s per capita GDP was about US$4,561. China had imported US$492.9 billion of goods from the US and exported five times that amount to the US over the decade, a difference of US$1.9 trillion.

Within minutes of first meeting Zhou in 1971, as they sat in the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse, Kissinger said to the older Chinese man, “We realise, of course, that there are deep ideological differences between us. You are dedicated to the belief that your concepts will prevail. We have our own convictions about the future. The essential question for our relations is whether both countries are willing to let history judge who is correct, while in the interval we cooperate on matters of mutual concern on a basis of mutual respect and equality and for the benefit of all mankind.”

Zhou responded, “It is very clear that the world outlook and stands of our two sides are different. As you just said, each side has its own convictions, and we both believe our ideas will become reality. But this shouldn’t hinder our two countries on the two sides of the Pacific Ocean seeking what you mentioned – a channel for coexistence, equality and friendship. The first question is that of equality, or in other words, the principle of reciprocity. All things must be done in a reciprocal manner.”

Today, China’s per capita GDP exceeds US$8,000. From 2011 through to 2017, China’s exports of goods to the US exceeded imports from the US by US$2.3 trillion. China’s economy is the world’s second largest, its military the largest, and its soft power, projected through economic means, global in reach. While Americans may criticise the means by which Beijing and China’s business elite acquired US technology, it was done largely in broad daylight, much not just with the acquiescence of Americans, but with their help.

This was what Trump was talking about when he tweeted in November last year, “I don’t blame China, I blame the incompetence of past Admins for allowing China to take advantage of the U.S. on trade leading up to a point where the U.S. is losing $100’s of billions. How can you blame China for taking advantage of people that had no clue? I would’ve done same!”

He reiterated this point in his Trumpian syntax in April, speaking to reporters. “Really, if you look at it, since the start of the World Trade Organisation, and they have really done a number on this country. And I don’t blame China. I blame the people running our country, I blame presidents. I blame representatives. I blame negotiators. We should have been able to do what they did. We didn’t do it. They did. And it’s the most lopsided set of trade rules, regulations that anybody’s ever seen.”

Calling Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama clueless was political hyperbole. They all could see what was happening. But actions taken by the latter two since China’s accession to the WTO were largely rifle shots at specific infractions made within the WTO’s dispute-resolution system. They took no big-picture action like Trump and focused little domestic political attention on the bilateral trading relationship.

Trump wages trade war against economics, and is sure to lose

A notable exception was Obama’s work on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a 12-nation trade pact, which China did not join and which could have offset some of its growing trade might in the region. In what seemed to many a move inconsistent with his goal to be tough with Beijing on trade, Trump pulled the US out of the TPP on his first day in office. But his point about his predecessors largely stands. There was ample evidence that IP protections and market access weren’t as advertised, but none made it a cornerstone issue of their presidency.

China’s leaders, from Deng onwards, focused and competent in building the national economy, have always made it clear where they were heading, and the acquisition of technology and know-how was critical to success in getting there. Deng’s goals, like extracting petroleum, producing steel and manufacturing vehicles, have evolved into higher order goals set by President Xi Jinping, who has spelled out in detail in his “Made in China 2025” plan the 10 key sectors on which the country will focus “to transform China from a manufacturing giant into a world manufacturing power”. From new information technology to new materials, and from aerospace equipment to power equipment, one can understand why a US administration might look at the list and ask, “Isn’t that supposed to be us?”

Beijing ‘closely watching’ Trump’s plan to restrict Chinese investments

Now that the China trade issue has had so much light shone on it and has caused bipartisan disquiet in the US, Trump and many in Congress seem determined to change organically the trade relationship between the two countries. It is hard to see how things can go back to business as usual or, if they do, that it will last long – too many Americans are aware of the issue now. The national security status the Trump administration has given the issue shows the seriousness and urgency with which they view it. Last month, the European Union filed its own complaint with the WTO, alleging certain IP practices “are inconsistent with China’s obligations under the WTO”.

The Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs on imports from China has been criticised by many as being “not the answer” to the trade issues the two countries are trying to resolve. Yet few seem to know what the answer is. The two systems may, in fact, be, as Lighthizer told Congress in 2010, incompatible. If nothing else, Trump’s volume and volubility about US trade issues with China have focused the attention of many on the issue.

How future trading between China and the US will take shape is one of the larger questions of our time.