日志

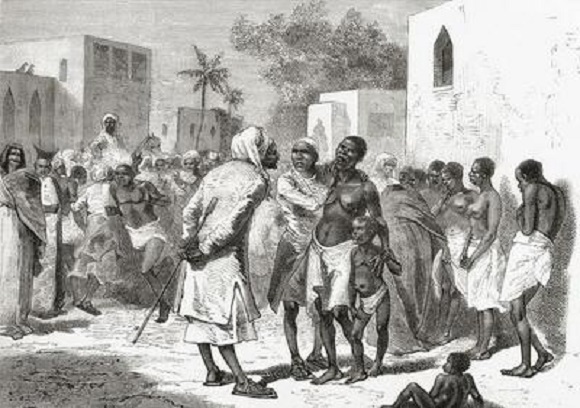

Europe and the People Without History 欧洲人的奴隶原产地

|

Born in Vienna, Austria in Feb. 01, 1923, died in Mar. 06, 1999. He was an anthropologist, the best known for his studies of peasants, Latin America, his advocacy of Marxian perspectives within anthropology; and book of the Europe and the People Without History.

Born in Vienna, Austria in Feb. 01, 1923, died in Mar. 06, 1999. He was an anthropologist, the best known for his studies of peasants, Latin America, his advocacy of Marxian perspectives within anthropology; and book of the Europe and the People Without History.1982, Europe and the People Without History

1969, Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century

1998, Envisioning Power: Ideologies of Dominance and Crisis

1959, Sons of the Shaking Earth: The People of Mexico and Guatemala--Their Land, History, and Culture

About the Europe and the People Without History

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520268180/europe-and-the-people-without-history

Offering insight and equal consideration into the societies of the "civilized" and "uncivilized" world, Europe and the People Without History deftly explores the historical trajectory of so-called modern globalization. In this foundational text about the development of the global political economy, Eric R. Wolf challenges the long-held anthropological notion that non-European cultures and peoples were isolated and static entities before the advent of European colonialism and imperialism. Ironically referred to as "the People Without History" by Wolf, these societies before active colonization possessed perpetually changing, reactionary cultures and were indeed just as intertwined into the processes of the pre-Columbian global economic system as their European counterparts. Utilizing Marxian concepts and a vivid consideration for the importance of history, Wolf judiciously traces the effects and conditions in Europe and the rest of the "known" world, beginning in 1400 AD, that allowed capitalism to emerge as the dominant ideology of the modern era.

Europe and the People Without History is a book by anthropologist Eric Wolf. First published in 1982, it focuses on the expansion of European societies in the Modern Era. "Europe and the people without history" is history written on a global scale, tracing the connections between communities, regions, peoples and nations that are usually treated as discrete subjects.[1]

A global history

The book begins in 1400 with a description of the trade routes a world traveller might have encountered, the people and societies they connected, and the civilizational processes trying to incorporate them. From this, Wolf traces the emergence of Europe as a global power, and the reorganization of particular world regions for the production of goods now meant for global consumption. Wolf differs from World Systems theory in that he sees the growth of Europe until the late eighteenth century operating in a tributory framework, and not capitalism. He examines the way that colonial state structures were created to protect tributary populations involved in the silver, fur and slave trades. Whole new "tribes" were created as they were incorporated into circuits of mercantile accumulation. The final section of the book deals with the transformation in these global networks as a result of the growth of capitalism with the industrial revolution. Factory production of textiles in England, for example transformed cotton production in the American south and Egypt, and eliminated textile production in India. All these transformations are connected in a single structural change. Each of the world's regions are examined in terms of the goods they produced in the global division of labour, as well as the mobilization and migration of whole populations (such as African slaves) to produce these goods. Wolf uses labor market segmentation to provide a historical account of the creation of ethnic segmentation.[2] Where World Systems theory had little to say about the periphery, Wolf's emphasis is on the people "without history" (i.e. not given a voice in western histories) and on how they were active participants in the creation of new cultural and social forms emerging in the context of commercial empire.[3]

Mode of production analysis

Wolf distinguishes between three modes of production: capitalist, kin-ordered, and tributary. Wolf does not view them as an evolutionary sequence. He begins with capitalism because he argues our understanding of kin-ordered and tributary modes is coloured by our understanding of capitalism. He argues they are not evolutionary precursors of capitalism, but the product of the encounter between the West and the Rest. In the tributary mode, direct producers possess their own means of production, but their surplus production is taken from them through extra economic means. This appropriation is usually by some form of strong or weak state.[4] In the kin-ordered mode of production, social labour is mobilized through kin relations (such as lineages), although his description makes its exact relations with tributary and capitalist modes unclear. The kin mode was further theorized by French structuralist Marxists in terms of 'articulated modes of production.' The kin-ordered mode is distinct again from Sahlins' formulation of the domestic mode of production.[5]

References

- Jump up^ Roseberry, William (1989). "European History and the Construction of Anthropological Subjects" in Anthropologies and Histories: essay in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 125.

- Jump up^ Roseberry, William (1989). "European History and the Construction of Anthropological Subjects" in Anthropologies and Histories: essay in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 127–9.

- Jump up^ Roseberry, William (1989). "European History and the Construction of Anthropological Subjects" in Anthropologies and Histories: essay in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 130.

- Jump up^ Roseberry, William (1989). "European History and the Construction of Anthropological Subjects" in Anthropologies and Histories: essay in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 131–2.

- Jump up^ Roseberry, William (1989). "European History and the Construction of Anthropological Subjects" in Anthropologies and Histories: essay in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 135.

[美] 埃里克·R·沃尔夫 2018-09-15 11:12

[美] 埃里克·R·沃尔夫 2018-09-15 11:12为什么非洲成为西半球奴隶的主要来源?为什么非洲成为欧洲人奴隶的主要来源,而不是欧洲自己成为欧洲人奴隶的主要来源?这个问题绝无清楚的答案,但其蛛丝马迹却日渐明显。前面已经提到,欧洲在公元第一个千年确曾供应奴隶给伊斯兰教徒和拜占庭人。在十字军东征的那几个世纪,伊斯兰教徒奴役基督徒,基督徒又奴役伊斯兰教徒。一直到15世纪末,在伊比利亚半岛上还是这个情形。13世纪,热那亚人和威尼斯人开始由黑海边的塔纳(Tana)进口突厥和蒙古奴隶,而14世纪大部分进口到欧洲的奴隶都是斯拉夫人和希腊人。14和15世纪,由这些地区进口的奴隶构成托斯卡纳(Tuscany)和加泰罗尼亚-阿拉贡人口的一个重要部分。而威尼斯的大部分财富来自奴隶贸易。虽然1386年以后在威尼斯奴隶不能用公开拍卖的方式被出售,但是在16世纪还是可以用私人契约的方式被出售。后来一直到17世纪,奴隶贸易还是地中海两岸海盗活动的一大部分。可是在欧洲,奴隶制度不完全是一种地中海现象。17与18世纪,苏格兰的矿工和盐场工人仍然受到奴役,有些工人的衣领还必须缝上其主人的姓名。此外,苏格兰和爱尔兰的战俘也被送到新世界做苦役(不过不是终身奴隶制度)。

再者,英国人十分倚重契约仆人在其新世界的殖民地上服劳役。所谓契约(Indenture)关系就是“ 各方面以一定条件在有限的时期中受制于一个人之下”。契约劳役事实上与奴隶制度相差无几。在契约约束下的契约仆人往往被人购买或出售,如果违反纪律,便受到严厉的责罚,许多人在契约期满以前便死了。这个情形和进口到加勒比海的非洲奴隶是一样的,这些奴隶出名的短寿。1607—1776年,每10个英属北美洲的契约仆人中,只有两个能活到其劳役届满,取得独立的农夫或工匠身份。他们大多在契约期满以前便死了,其余的变成按日计酬的散工或贫民。18世纪末,服务契约在北美发展到最高峰。服务契约苦役对雇主可能有些好处,因为契约仆人的成本不及奴隶的成本。可是在同时,服务契约有期限,受到习惯与法律的限制,仆人也比较容易逃脱。不过,我们不应过分高估法律或意识形态对奴役欧洲人的约束力量。为什么欧洲人未被合法地奴役,是一个尚未被解答的问题。每当诉诸基督教的平等不够用时,或许重商主义者主张保全国内人力的想法,便发生作用。在新世界的系统中,欧洲有时限的奴仆与非洲终身奴隶之间的区别,便在无数法律和社会系统中将白人和黑人分开。

在北美洲日后叫作南卡罗来纳的地方,英国殖民者由原住民人口中取得印第安人奴隶(战俘)和鹿皮,并以欧洲的商品报偿猎奴的群体。纳什说:英国人“把战争转包给”印第安人。他们挑拨威斯托斯人(Westos)反对内陆的人;肖尼人反对威斯托斯人;克里克人反对提默夸人(Timucua)、瓜尔斯人(Guales)和阿巴拉契人(1704年,这些族群中有 1 万人被输出为奴隶);卡托巴人(Catawba)反对肖尼人;卡托巴人、康加里人(Congarees)和肖尼人反对切罗基人;切罗基人什么人都反对。在1715—1717年的雅玛西人(Yamasee)战争中,卡罗来纳的印第安人奴隶贸易达到最高峰,此后便走下坡路了。

欧洲人之所以喜欢非洲奴隶甚于喜欢美洲原住民奴隶,一般的说法是非洲劳工比较好,比较可靠。到了18世纪20年代,非洲奴隶的价格已经比印第安奴隶为高。可是主要的因素却是印第安奴隶因为住得离其原住民群体近,容易反叛,也常脱逃。英国殖民者也害怕以印第安人为奴隶,会疏远对西班牙人和法国人作战的美洲原住民盟邦。最后,欧洲人也可以请美洲原住民帮忙,将逃走的非洲奴隶抓回来归还主人。譬如,1730年,切罗基人签约捕捉和归还逃走的奴隶,代价是每归还一名奴隶由欧洲人付一支枪和一件斗篷。

虽然契约白人仆人和美洲原住民奴隶多少可以由其自己的族群中得到一点支持,但是非洲奴隶的这种支援却被剥夺。在非洲一端,奴隶被捕捉或出售,远离自己的亲属和邻居;在到达美洲的港埠以后,欧洲人又有意将不同民族和语言的非洲奴隶混合,以防止他们团结一致。一旦有了指派的主子以后,由于法律上的歧视和种族主义感情的发展,他们与白人契约仆人和美洲原住民之间的隔离被确立下来。如果他们脱逃,则任何想领赏的“ 巡逻者”,都可以用他们的肤色为识别标志。因而,奴役非洲人得到的劳力,可以在奴隶主的指挥下不断做辛勤的工作,法律与习俗的约束减低到最小的程度。它排除了新世界其他劳动人口群成为奴隶的可能。

那么,为什么是非洲?在葡萄牙人和西班牙人探索大西洋地区的时候,地中海的奴隶贸易十分频繁。可是不久以后,由于1453年奥斯曼帝国攻占了君士坦丁堡,而随后土耳其人又封锁了去东方的路线,地中海西部地区不再能由地中海东部地区和黑海四周取得奴隶。那个时候,葡萄牙人已经开始在非洲的西海岸从事奴隶贩卖,尼德兰人、法国人和英国人只不过是学步葡萄牙人。1562年约翰·霍金斯(John Hawkins)在初次出航时,在加那利群岛听人说:“黑人在伊斯帕尼奥拉岛(Hispaniola)是一种很好销的商品。”奴隶贸易有利可图的观念,无疑激励了他得到那枚盾形勋章,那枚勋章上刻着一个被绑住的摩尔人俘虏的半身像。

非洲的背景

虽然霍金斯听人说“在几内亚海岸可以得到大量的黑人”,但是非洲当时的人口事实上增长得并不快。由塞内加尔北界到今日尼日利亚的东界,1500年人口估计在1100万左右。那时候非洲的中西部(赤道几内亚、扎伊尔和安哥拉)约有800万居民。到了1800年,西非人口约有2000万,非洲中西部的人口约有1000万。这两个地区人口的增加,可能是美洲农作物引入的结果,如玉蜀黍和木薯。因而,这个地区能维持大规模的人口贸易,以及在欧洲需求与非洲供应之间运输系统的迅速发展,都是出人意料的。这种发展是欧洲的主动与非洲的合作配合而成。欧洲人出资主办奴隶贸易。捕捉、运送以及对俘虏在等待运送出洋期间的控制和供养,大多由非洲人经手。欧洲人负责将俘虏运送出洋、让他们习惯新环境,以及到了目的地出售俘虏。

这种新贸易发生的所在地,其社会都有相似的生态基础。它们以砍烧方式种植块茎、香蕉、粟和高粱,也养牲畜。(由于采采蝇的猖獗,大半森林地带不适宜养牛马。)制铁工匠供应铁锄、铁斧以及矛尖和剑。通过广大的交易网络和市场,各地的人交易许多工艺制品与铁矿、红铜、盐和棕榈产品等地方性原材料。世系群代表祖先与后裔间的继续合作,并控制了土地与其他资源的取得。这些世系群由长老统治。长老以新娘聘礼交换对妇女生殖能力及其子孙的控制权,也因此实践世系群间的联盟。在这种适应中缺乏的不是土地,而是劳力。长老以世系群代表的资格操纵亲属关系的安排,而掌握对劳力的使用权。

虽然这些相互影响的世系群往往形成自主的社会与经济体系,但是也有罩在许多世系群上方的政体。统治这种政体的是“ 神王”,其本人具体表现超自然的身份与属性。在这种仪式性王权与皇家控制最重要资源(如黄金、铁矿床、盐和奴隶)和对长距离贸易管辖权结合的地方,出现了更复杂的“ 金字塔式”政治结构。这些政体通过神话故事,可以表明为首的世系群追溯至超自然力的主要中心。但是沿由非洲森林地带到地中海沿岸地区贸易路线的各人口群,其间不断改变的关系,对于上述政体的形成,或许有密切的关系。战事和涉足长程贸易造成的政治统一,使从事战争和贸易的精英分子发达,使若干地方世系群结合起来环绕一个皇家中心。如此而造成的政治“ 金字塔”,建筑在一个相当自治的农业基础之上。但是其统治阶层却集合军事和经济资源,把这些资源集中在皇家的朝廷。地方性以亲属关系原则组成的世系群,对于土地和劳力保留相当大的控制权,不过在战争与贸易上却服从皇家中心。权力如此分配,也使主管地方上土地和新娘聘礼经济的“ 长老”,将其利害关系与皇家世系群仪式与贸易精英分子范围较广大的利害关系结合起来。(这种相融或许反映在流行的意识形态之中,也就是说不将权力授权他人,而主要是参与和分享。)关键性垄断权的发展、战争的加剧以及长程贸易的扩展,可以扩大社会政治的金字塔。外来的侵略或脱离又可使之缩小。因而,这样的金字塔系统容易遭受外人的征服或渗透。

与欧洲人的接触引进了金属、金属器皿、枪炮和火药、纺织品、朗姆酒和烟草。它在两点上影响到这样的金字塔体系。第一点是主宰联姻与分配子孙的那些知名货物的流通。第二点是精英分子的消耗,也就是长程贸易的关系的顶点。因而我们可以说欧洲的扩张吻合原先存在的非洲交易系统,没有改变其基本的结构,只不过是将许多货物注入了非洲的交易系统。但是这样的遭遇还有另一个方面,而它不久就不但影响到流通,也影响到劳力的分配。只要欧洲人只是想得到胡椒或黄金或明矾,奴隶制度的问题便是次要的。但是不久因为欧洲要求以进口的货物交易非洲人,生产关系的本身便受到影响。

新生的奴隶贸易无疑对供应地区造成政治上的影响,尤其是因为欧洲人自己很少动手捕捉奴隶。17世纪晚期,法国代理商让·巴伯特(Jean Barbot)说,欧洲人依靠的是非洲的“ 国王、富人和第一流的商人”。而非洲的合作又加强了已有的国家政权,并在欧洲影响力到来以前没有国家的地区促成国家的建立。

在欧洲人来到非洲以前,两个日后对奴隶贸易有重要作用的地区,已经在非洲国家的控制之下。其中一个是刚果王国(Kingdom of Kongo)。据说刚果王国建于14世纪下半叶,若干源于刚果河以北的高级亲属群体,主宰了刚果河以南的人口。第二个在欧洲人到来以前已有国家的地区是尼日利亚南部的贝宁。贝宁的统治者和日后奥约王国、达荷美王国(Dahomey)的统治者一样,说自己的世系可以追溯到约鲁巴族的圣地伊莱-伊费(Ile-Ife),与尼日尔更东面和北面的地区有关系。

在另外两个地区,国家的形成是在与欧洲人接触以后。一个地区是在刚果王国以东,其中心在基萨莱湖(Lake Kisale)四周,在上刚果河区域。这是卢巴-隆达人在17世纪初年以后扩张的心脏地带。而这种扩张的开启是受到葡萄牙人开发大西洋海岸所造成的经济刺激。第二个在欧洲人到来以后才形成国家的地区是黄金海岸。17世纪末叶,阿善提人势力增长,扫除了几个较小的政体。

奴役的机制

奴隶是些什么人?是用什么方法使他们成为奴隶的?在欧洲人到来以前,一个自由人变成潜在的奴隶的方法有三个:人质的制度,在司法上使一个人脱离其世系群的保护以及为取得俘虏而打仗。

人质的方法用得很广。偿付债务用抵押,即把一个人归于另一个人所有以偿付债务。在抵押期间,收债者对接收到的这个人的劳力、生殖活动和子孙都有权控制。人也可以在饥荒的时候抵押自己和自己的亲戚,以对人的权力交易食物。

第二个成为潜在奴隶的方法是通过司法来运作。简言之,违反亲属关系秩序和世系群结构的行为,被视为不但反抗活人,也反抗祖先,因而也就是反抗超自然。当为了处罚一项犯罪而将一个人由其世系群开除时,这个人非但再得不到其亲属的支持,而且也被宣布为违反超自然的秩序。在某种意义上,亲属关系秩序为了自我保护,将向它挑战的人置于它的领域以外。这样的人可以被卖为奴。当奴隶主的世系群或姻亲使用权力避免自己被指控时,也可以让奴隶代他们受过。

第三个办法是抓战俘。和其他的方法一样,受害人实际上也被强迫与其本土的世系群断绝关系,失去亲人的支持。因此,一般而言,不论是人质、罪犯或战俘,取得潜在奴隶的方法都是断绝他们与亲人的关系,并把他们转交到奴隶主的亲属群体手中。

应该注意的是,人质或奴隶一旦为其主人世系群所有,即使否认他们与主人的世系群有关联,在家族团体中却可以成为一个有作用的分子。因而人质和奴隶制度也可以有比较良好的结果,不像西半球特有的那种“动产奴隶制度”(Chattel Slavery)。不过人质和奴隶却也都没有世系群分子所有的权利,因而由其奴隶主任意摆布。玛丽·道格拉斯(Mary Douglas)曾经指出 ,这种操纵奴隶的能力在母方组成的社会结构中如何发挥特别重要的作用:

一个女性人质可以生产其他家族的世系群分子,不过这些子女可望住在其主人的村落中, 并受他的控制。他可以把这个女性人质的女儿许配给自己年轻的族人为妻,而建立他在当地的家族分支。她生下的儿子也将是他的人质,他可以说服他们住在他的村子中,他可以把自己家族中的女子许配给他们为妻, 使他们不去找自己母亲的兄弟。 人质的主人之间也可以缔结联盟,使许多不同家族的人质结合。

再者,在一夫多妻制的情形下,人质可以带给世系群长老更大的权力,因为长老控制妇女与新娘聘礼的分配。

在培养家族团体的层次与在精英分子管理的层次,所有这些方法都有不同的作用。酋长和最高统治者取得的人质、罪犯和战俘,不会变成家族团体的成员。相反,他们被指派在酋长的种植园中和皇家的金矿上工作,以及在长程贸易中运输货物。商人也用奴隶供给沿贸易路线的商队站食物,或担任挑夫。因此,对军事、司法和商业精英分子来说,奴隶劳力供应他

们生活所需剩余物质中的绝大部分,以及与他们精英身份相称的货物与服务。因而战争与司法控制同时被用来扩大奴隶阶级,以其劳力支持精英分子的各种特权。

这三种机制也都用来供应奴隶贸易中的奴隶。如此一来,原来已有的制度便为欧洲的商业扩张所用。非洲各社会专事运送奴隶,专事奴隶贸易中海岸与内地间的运输。为了研究奴隶贸易的细节与它对当地人口群的影响,我们将集中讨论两个地区。这两个地区大批供应输往西半球的奴隶:西非(尤其是黄金海岸、奴隶海岸和尼日尔河三角洲)和中非(也就是奴隶登记簿中“安哥拉人”和“刚果人”的来源地)。

(本文选摘自《欧洲与没有历史的人》,[美]埃里克·R·沃尔夫 著,贾士蘅 译,后浪丨民主与建设出版社,2018年8月。经授权,澎湃新闻转载,现标题为编者所拟。)

Eric Wolf From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Early life

Life in Vienna

Wolf was born in Vienna, Austria to a Jewish family. Wolf has described his family as nonreligious, and said that he had little experience of a Jewish community while growing up. His father worked for a corporation and was also a Freemason. Wolf described his mother, who had studied medicine in Russia, as a feminist—"not in terms of declarations, but in terms of her stand on human possibilities." In 1933, his father's work moved the family toSudetenland, Czechoslovakia, where Wolf attended GermanGymnasium. He describes his life in the 1920s and 30s in segregated Vienna and then in proletarianizing Czechoslovakia as attuning him early on to questions surrounding class, ethnicity, and political power. The social divisions in Vienna and conflicts in the region in the 1930s influenced Wolf's later scholarly work.[citation needed]

Studying and living in other countries

Wolf and his family moved to England and then to the United Statesto escape Nazism. Wolf went to the Forest School, in Walthamstow, Essex, for two years,[2] where he learned English and became interested in science, in part because of the strong emphasis on science of the school's Canadian headmaster. Despite learning English only when he arrived at the school as a teenager, he won the school's English essay prize. Moving to England also made him aware of cultural difference in a new way. In 1940, Wolf was interned in an alien detention camp in Huyton, nearLiverpool, England. The detention camp was a high stress environment. It was there that Wolf became exposed to the organizational possibilities of socialism and communism. Through seminars organized by intellectuals in the camp, he was also exposed to the social sciences. Wolf was especially influenced by the German Jewish sociologist Norbert Eliaswho was also interned there.

Later in 1940, Wolf emigrated to the United States—the same period that 300,000 Jews emigrated to the U.S. from Germany. He enrolled in Queens College in New York City and also spent a summer at the Highlander Folk School inTennessee in 1941. Spending time in the South allowed Wolf to see a different side of the United States than he was familiar with from New York, and was particularly interested the internal inequalities of the United States that the South made apparent. Partway through college, he joined the army and fought overseas in World War II, serving in Italy with the 10th Mountain Division. After returning from Europe, Wolf finished college at Queens. There, Wolf became interested in anthropology, and later went on to study anthropology at Columbia University.[citation needed]

Career

Columbia had been the home of Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict for many years, and was the central location for the spread of anthropology in America. By the time Wolf had arrived Boas had died and his anthropological style, which was suspicious of generalization and preferred detailed studies of particular subjects, was also out of fashion. The new chair of the anthropology department was Julian Steward, a student of Robert Lowie and Alfred Kroeber. Steward was interested in creating a scientific anthropology which explained how societies evolved and adapted to their physical environment.

Wolf was one of the coterie of students who developed around Steward. Older students' leftist beliefs, Marxist in orientation, worked well with Steward's less politicized evolutionism. Many anthropologists prominent in the 1980s such as Sidney Mintz, Morton Fried, Elman Service, Stanley Diamond, and Robert F. Murphy were among this group.

Wolf's dissertation research was carried out as part of Steward's 'People of Puerto Rico' project. Soon after, in 1961, Wolf began teaching at the University of Michigan, holding a position as a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and Chair of the Department of Anthropology at Lehman College, CUNY[3] before moving in 1971 to the CUNY Graduate Center, where he spent the remainder of his career. In addition to his Latin American work, Wolf also did fieldwork in Europe.

Wolf's key contributions to anthropology are related to his focus on issues of power, politics, and colonialism during the 1970s and 1980s when these topics were moving to the center of disciplinary concerns. His most well-known book,Europe and the People Without History, is famous for critiquing popular European history for largely ignoring historical actors outside the ruling classes. He also demonstrates that non-Europeans were active participants in global processes like the fur and slave trades and so were not 'frozen in time' or 'isolated' but had always been deeply implicated in world history.

Towards the end of his life he warned of the 'intellectual deforestation' that occurred when anthropology focused on high-flown theory instead of sticking to the realities of life and fieldwork. Wolf struggled with cancer later in life. He died in 1999 in Irvington, New York.

Work and ideas

Disciplinary imperialism

As a social scientist, already fighting from a less than ideal position in the wider academy, Eric Wolf criticized what he called disciplinary imperialism within social sciences, and between social sciences on one hand, and the natural sciences on another, banishing certain topics, such as history, as not enough academic. An example within social sciences is cultural anthropology winning over social anthropology (established in British academia), over sociology, and over history in the American and Americanized global academic community, since sociology was left with studying social mobility and social class, categories which neoliberals argue to be irrelevant, cultural anthropologists on the other hand proved useful for colonialist rule over "peoples without history", studying their myths, values, etc. This can be seen in mobilization of anthropologists for work with the U.S. military and Pentagon worldwide.[4] His 1982 Europe and the People Without History reflected a turn away from, or fight against the disciplinary imperialism by dismantling ideas such as historical vs. non-historical people and societies, focusing on the relationship between European expansion and historical processes in the rest of the world—charting a global history, beginning in the 15th century. As reflected in the title of the book, he is interested in demonstrating ways in which societies written out of European histories were and are deeply involved in global historical systems and changes [5]

Power

Much of Wolf's work deals with issues of power. In his book Envisioning Power: Ideologies of Dominance and Crisis(1999), Wolf deals with the relationship between power and ideas. He distinguishes between four modalities of power: 1. Power inherent in an individual; 2. Power as capacity of ego to impose one's will on alter; 3. Power as control over the contexts in which people interact; 4. Structural power: "By this I mean the power manifest in relationships that not only operates within settings and domains but also organizes and orchestrates the settings themselves, and that specifies the direction and distribution of energy flows". Based on Wolf's previous experience and later studies, he rejects the concept of culture that emerged from the counter-Enlightenment. Instead, he proposes a redefinition of culture that emphasizes power, diversity, ambiguity, contradiction and imperfectly shared meaning and knowledge.[6]

Marxism

Wolf, known for his interest in and contributions to Marxist thought in anthropology, says that Marxism must be understood in the context of kinship and local culture. Culture and power are integrated, and mediated by ideology and property relations. There are two branches of Marxism, as defined by Wolf: Systems Marxism and Promethean Marxism. Systems Marxism is the discipline of postulates that could be used to frame general laws or patterns of social development. Promethean Marxism symbolized optimism for freedom from economic and political mistreatment and renowned reforming as the fashion to a more desirable future.[7]

Personal

Wolf had two children from his first marriage, David and Daniel. Wolf later married the anthropologist Sydel Silverman.[8]in the 1960s his best friend was the anthropologist Robert Burns Jr., father of the documentarian Ken Burns. While Ken Burns's mother was dying, he was cared for by Wolf's family.[9]

Published works

- The Mexican Bajío in the 18th Century (Tulane University, Middle American Research Institute, 1955)

- Sons of the Shaking Earth (University of Chicago Press, 1959)

- Anthropology (Prentice-Hall, 1964)

- Peasants (Prentice-Hall, 1966)

- Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century (Harper & Row, 1969)

- Wrote Introduction and contributing essay in National Liberation : revolution in the third world / Edited by Norman Miller and Roderick Aya (The Free Press, 1971)

- The Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley (with John W. Cole) (Academic Press, 1974)

- Europe and the People Without History (University of California Press, 1982)

- Envisioning Power: Ideologies of Dominance and Crisis (University of California Press, 1999)

- Pathways of Power: Building an Anthropology of the Modern World (with Sydel Silverman) (University of California Press, 2001)