4. Discussion

Disturbances of host microbiota are associated with intestinal disorders that causes with tissue damage and exacerbated immune responses. Alternative approaches aimed at the modulation of mucosal inflammation are fundamental for the control of relapsing chronic diseases that may present with reduced responsiveness to conventional therapies, such as IBD. Hence, since increasing evidence suggests that MLT could play an important role in the relationship between inflammation and gut microbiota [28], we explored its potential modulatory effects in intestinal homeostasis.

MLT is a tryptophan-derived molecule that influences not only circadian rhythm, but also microbial metabolism and leukocyte responses, including the regulation of B and T cells activation [29]. The use of MLT as a possible adjunctive treatment for intestinal diseases has been reported; however, there is no consensus and some studies point to controversial effects on IBD. Furthermore, the exact mechanisms by which the hormone acts on gut immunity are still unclear. Intriguingly, here, we showed that MLT treatment of experimental colitis led to the worsening, instead of the amelioration, of gut inflammation.

The utilization of MLT in experimental models of colitis [30,31,32,33], for a short period of time or at low dosages, was described as beneficial in constraining inflammation. However, in the chronic treatment of TNBS-induced colitis, and in some cases of patients presenting UC or CD, there was a deterioration in intestinal inflammation upon MLT utilization [19,34,35]. Indeed, despite some supposedly beneficial effects described in the literature [36], here, we observed a potentiation of intestinal inflammation in MLT-treated mice, which was dependent on the host gut microbiota.

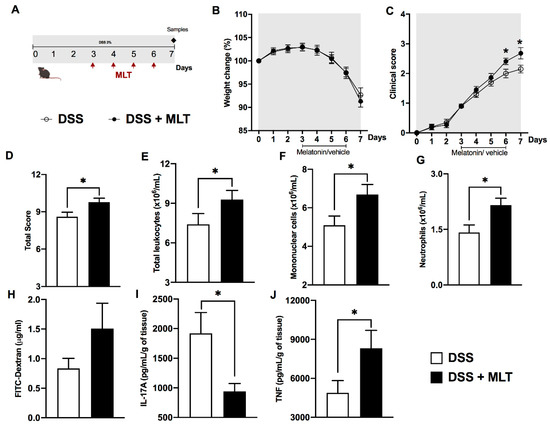

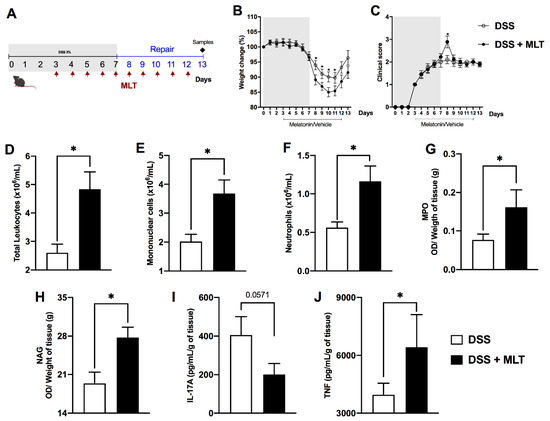

In our second experimental design, mice were evaluated in the acute phase of inflammation after a four-day MLT administration that was initiated upon the symptom’s onset. Clinical signs, systemic and gut inflammation were accentuated in the hormone-treated group, suggesting a harmful effect on colitis. Differently, in Wistar rats exposed to TNBS, a prophylactic administration of MLT followed by short-term treatment during acute inflammation led to colitis amelioration [35]. On the other hand, the chronic treatment induced the opposite outcome and was in accordance with our findings of a more notable disease worsening in the third experimental design, which included a clear difficulty in weight regaining after DSS withdrawal.

The impaired clinical recovery in both acute and repair phases of colitis in mice treated with MLT could be linked to the increase in circulating leukocyte and TNF production in the colon, despite reduced IL-17 cytokine, which is fundamental for gut immunity in the control of bacteria burden [9]. Corroborating our data, MLT was able to inhibit the differentiation of Th17 cells in an experimental model of necrotizing enterocolitis [37] and, in autoimmune uveitis, MLT suppressed Th17 differentiation through the reactive-oxygen species–TXNIP-HIF1α axis [38]. On the other hand, cytokines with an inflammatory profile intensify mucosal effector responses, though a consequent deterioration in the intestinal lamina propria due to excessive inflammation may occur [39].

The increased number of blood monocytes and neutrophils, besides augmenting myeloperoxidase and macrophages’ activity in the gut of mice exposed to DSS and treated with MLT, is suggestive of inflammation induction and its long-term persistence. Together with the elevated TNF, these findings may point to an important host response to the intestinal dysbiosis and bacteria replication. In fact, macrophages play fundamental functions in the gut, including the resistance to microbiota translocation through the damaged gut barrier and control of intracellular infections. Moreover, circulating blood monocytes are able to increase IL-1β production before migration to the inflamed colon, where these cells are important sources of both IL-1β and TNF [40]. In addition, the neutrophil population, which is also responsible for bacteria elimination, may be markedly increased in the blood and mucosa of IBD patients or in experimental colitis, though its excessive or uncontrolled responses could lead to tissue damage [41,42,43].

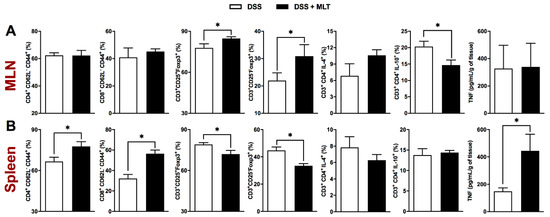

The balance between effector, memory and regulatory T lymphocyte populations drive the main cellular responses associated with inflammation and antigen clearance [44,45]. Here, we showed that during disease remission, mice treated with MLT had a higher frequency of effector memory CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes (TEM) in the spleen, a finding that could be related to reduced regulatory responses by Foxp3+ cells in the same lymphoid organ. In accordance, circulating colitogenic CD4 TEM cells have been observed during experimental colitis [46], indicating that sites other than the intestine may present pathogenic lymphocytes able to maintain chronic inflammation. Nevertheless, though the CD3+Foxp3+ MLN cells were decreased, the concomitant reduction in IL-10 producing lymphocytes at these draining lymph nodes, together with an outstanding splenic TNF production, reiterates the pro-inflammatory potential of MLT in experimental colitis. In line with that, TNF plays a fundamental role in intestinal inflammation as well as in other immune-mediated diseases [47,48].

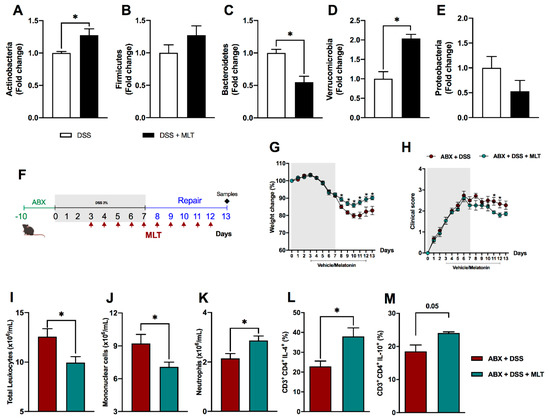

In addition to the uncontrolled immune response, which can be influenced by genetic and environmental factors, the microbiota is a key element in IBD pathogenesis [49]. These diseases usually present with decreased microbial diversity and gut dysbiosis [50]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii from the Firmicutes phylum and Bacteroidetes are frequently reduced in Crohn’s disease patients, while Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria are commonly increased in comparison to healthy individuals [51,52]. These bacteria translocate through the intestinal epithelium and replicate, causing inflammation [53].

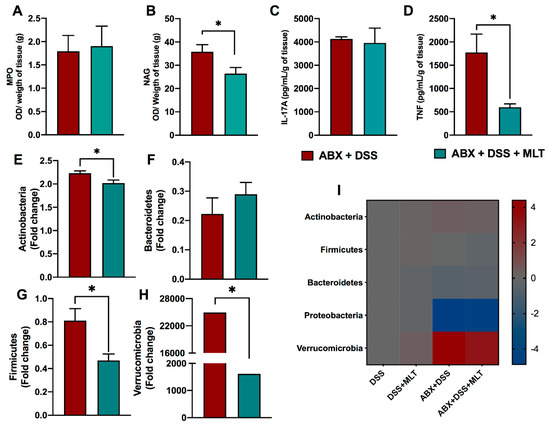

Here, we observed that MLT treatment of colitis-recovering mice led to augmented Actinobacteria in contrast to reduced Bacteroidetes phyla, compared to vehicle treated animals, thus confirming the impairment of gut homeostasis caused by the hormone. Curiously, a consistent augmented expression of the Verrucomicrobia phylum was observed upon MLT treatment, indicating that Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucin-degrading bacteria, could be involved in the exacerbation of colitis inflammation in mice with the hormone supplementation [54]. Indeed, the microbiota depletion by a wide-range antibiotic therapy before MLT treatment reversed the main inflammatory and clinical parameters associated with colitis deterioration. These findings were accompanied by a reduction in Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobia phyla.

The degradation of mucin by gut bacteria may facilitate IBD onset, due to a facilitation of microbes or antigen access to the gut mucosa, where the local inflammatory response is rapidly triggered. A. muciniphila bacteria, a representative of the Verrucomicrobia phylum, worsen the gut inflammatory responses induced by S. typhimurium by interfering with local mucus homeostasis [55]. Interestingly, a recent study reported different modulations of gut inflammation dependent on Akkermansia muciniphila strains; i.e., while the FSDLZ36M5 isolate protected against colitis, the strains FSDLZ39M14, ATCC BAA-835 and FSDLZ20M4 were not able to induce these beneficial effects. Then, the protective effects assigned to A. muciniphila in DSS colitis are strain specific [56]. Indeed, A. muciniphila play a dual role in the gut immunity. Despite these bacteria being widely known to constrain the inflammatory response, the opposite effect may occur in mice presenting colorectal cancer, in gnotobiotic animals harboring a specific pathogen or in certain gene deletions, such as in mice not presenting the gene coding for IL-10 [57]. To provide more detail, these bacteria are able to induce spontaneous colitis in germ-free IL10−/− mice, whereas NLRP6 limits their colonization and protects against colitis [57]. Moreover, the replenishment of mice with A. muciniphila after antibiotic therapy in colitis associated with colorectal cancer led to damage in the gut barrier, increased bacterial (LPS) translocation as well as augmented local and systemic inflammatory responses [58]. Then, under these conditions, A. muciniphila may lead to the worsening of intestinal inflammation [59], thus corroborating our evidence.

As discussed above, our findings are contrary to some previous studies and pointed to an activation effect of MLT on gut immunity, which was dependent on the local microbiota. It is known that mice bred or housed in different facilities may differ in their microbiota and this possibility cannot be ruled out while considering the opposing results presented here. Another innovation of our study is the hormone supplementation only after the initial establishment of the colitis signs, i.e., after the breakdown of mucosal immunity, but before the most severe diseases. In addition, our data are consistent in showing that the immunological parameters corroborated the worsening of gut inflammation in mice treated with MLT, despite the known anti-oxidant effects of this hormone [60]. Interestingly, the mice under the hormonal supplementation not only presented notable signs of colitis aggravation or delayed recovery, but also increased markers of exacerbated inflammatory response. These findings confirmed the deleterious effects of MLT on a previously disrupted gut barrier, indicating that the hormone may have a direct or indirect role in shaping the gut microbiota or the immune response raised to constrain the local dysbiosis. Nevertheless, the amplification of local inflammation may have an undesirable potential to cause persistent tissue damage and intestinal damage.

In conclusion, despite the fact that MLT could play a protective role in specific conditions of inflammation, we still should be cautious regarding its wide use to treat IBD, since hormone supplementation may exacerbate the inflammatory responses, depending on the hosts and on the gut microbiota harbored by them.