The creation of the U.S. Forest Service at the turn of the twentieth century was the premier example of American state building during the Progressive Era. Prior to the passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883, public offices in the United States had been allocated by political parties on the basis of patronage. The Forest Service, in contrast, was the prototype of a new model of merit-based bureaucracy. It was staffed with university-educated agronomists and foresters chosen on the basis of competence and technical expertise, and its defining struggle was the successful effort by its initial leader, Gifford Pinchot, to secure bureaucratic autonomy and escape routine interference by Congress. At the time, the idea that forestry professionals, rather than politicians, should manage public lands and handle the department’s staffing was revolutionary, but it was vindicated by the service’s impressive performance. Several major academic studies have treated its early decades as a classic case of successful public administration.

Today, however, many regard the Forest Service as a highly dysfunctional bureaucracy performing an outmoded mission with the wrong tools. It is still staffed by professional foresters, many highly dedicated to the agency’s mission, but it has lost a great deal of the autonomy it won under Pinchot. It operates under multiple and often contradictory mandates from Congress and the courts and costs taxpayers a substantial amount of money while achieving questionable aims. The service’s internal decision-making system is often gridlocked, and the high degree of staff morale and cohesion that Pinchot worked so hard to foster has been lost. These days, books are written arguing that the Forest Service ought to be abolished altogether. If the Forest Service’s creation exemplified the development of the modern American state, its decline exemplifies that state’s decay.

Civil service reform in the late nineteenth century was promoted by academics and activists such as Francis Lieber, Woodrow Wilson, and Frank Goodnow, who believed in the ability of modern natural science to solve human problems. Wilson, like his contemporary Max Weber, distinguished between politics and administration. Politics, he argued, was a domain of final ends, subject to democratic contestation, but administration was a realm of implementation, which could be studied empirically and subjected to scientific analysis.

The belief that public administration could be turned into a science now seems naive and misplaced. But back then, even in advanced countries, governments were run largely by political hacks or corrupt municipal bosses, so it was perfectly reasonable to demand that public officials be selected on the basis of education and merit rather than cronyism. The problem with scientific management is that even the most qualified scientists of the day occasionally get things wrong, and sometimes in a big way. And unfortunately, this is what happened to the Forest Service with regard to what ended up becoming one of its crucial missions, the fighting of forest fires.

Pinchot had created a high-quality agency devoted to one basic goal: managing the sustainable exploitation of forest resources. The Great Idaho Fire of 1910, however, burned some three million acres and killed at least 85 people, and the subsequent political outcry led the Forest Service to focus increasingly not just on timber harvesting but also on wildfire suppression. Yet the early proponents of scientific forestry didn’t properly understand the role of fires in woodland ecology. Forest fires are a natural occurrence and serve an important function in maintaining the health of western forests. Shade-intolerant trees, such as ponderosa pines, lodgepole pines, and giant sequoias, require periodic fires to clear areas in which they can regenerate, and once fires were suppressed, these trees were invaded by species such as the Douglas fir. (Lodgepole pines actually require fires to propagate their seeds.) Over the years, many American forests developed high tree densities and huge buildups of dry understory, so that when fires did occur, they became much larger and more destructive.

After catastrophes such as the huge Yellowstone fires in 1988, which ended up burning nearly 800,000 acres in the park and took several months to control, the public began to take notice. Ecologists began criticizing the very objective of fire prevention, and in the mid-1990s, the Forest Service reversed course and officially adopted a “let burn” approach. But years of misguided policies could not simply be erased, since so many forests had become gigantic tinderboxes.

As a result of population growth in the American West, moreover, in the later decades of the twentieth century, many more people began living in areas vulnerable to wildfires. As are people choosing to live on floodplains or on barrier islands, so these individuals were exposing themselves to undue risks that were mitigated by what essentially was government-subsidized insurance. Through their elected representatives, they lobbied hard to make sure the Forest Service and other federal agencies responsible for forest management were given the resources to continue fighting fires that could threaten their property. Under these circumstances, rational cost-benefit analysis proved difficult, and rather than try to justify a decision not to act, the government could easily end up spending $1 million to protect a $100,000 home.

Mission on the move: fighting flames near Camp Mather, California, August 2013. (Reuters / Max Whittaker)

While all this was going on, the original mission of the Forest Service was eroding. Timber harvests in national forests, for example, plunged, from roughly 11 billion to roughly three billion board feet per year in the 1990s alone. This was due partly to the changing economics of the timber industry, but it was also due to a change in national values. With the rise of environmental consciousness, natural forests were increasingly seen as havens to be protected for their own sake, not economic resources to be exploited. And even in terms of economic exploitation, the Forest Service had not been doing a good job. Timber was being marketed at well below the costs of operations; the agency’s timber pricing was inefficient; and as with all government agencies, the Forest Service had an incentive to increase its costs rather than contain them.

The Forest Service’s performance deteriorated, in short, because it lost the autonomy it had gained under Pinchot. The problem began with the displacement of a single departmental mission by multiple and potentially conflicting ones. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, firefighting began to displace timber exploitation, but then firefighting itself became controversial and was displaced by conservation. None of the old missions was discarded, however, and each attracted outside interest groups that supported different departmental factions: consumers of timber, homeowners, real estate developers, environmentalists, aspiring firefighters, and so forth. Congress, meanwhile, which had been excluded from the micromanagement of land sales under Pinchot, reinserted itself by issuing various legislative mandates, forcing the Forest Service to pursue several different goals, some of them at odds with one another.

Thus, the small, cohesive agency created by Pinchot and celebrated by scholars slowly evolved into a large, Balkanized one. It became subject to many of the maladies affecting government agencies more generally: its officials came to be more interested in protecting their budgets and jobs than in the efficient performance of their mission. And they clung to old mandates even when both science and the society around them were changing.

The story of the U.S. Forest Service is not an isolated case but representative of a broader trend of political decay; public administration specialists have documented a steady deterioration in the overall quality of American government for more than a generation. In many ways, the U.S. bureaucracy has moved away from the Weberian ideal of an energetic and efficient organization staffed by people chosen for their ability and technical knowledge. The system as a whole is less merit-based: rather than coming from top schools, 45 percent of recent new hires to the federal service are veterans, as mandated by Congress. And a number of surveys of the federal work force paint a depressing picture. According to the scholar Paul Light, “Federal employees appear to be more motivated by compensation than mission, ensnared in careers that cannot compete with business and nonprofits, troubled by the lack of resources to do their jobs, dissatisfied with the rewards for a job well done and the lack of consequences for a job done poorly, and unwilling to trust their own organizations.”

WHY INSTITUTIONS DECAY

In his classic work Political Order in Changing Societies, the political scientist Samuel Huntington used the term “political decay” to explain political instability in many newly independent countries after World War II. Huntington argued that socioeconomic modernization caused problems for traditional political orders, leading to the mobilization of new social groups whose participation could not be accommodated by existing political institutions. Political decay was caused by the inability of institutions to adapt to changing circumstances. Decay was thus in many ways a condition of political development: the old had to break down in order to make way for the new. But the transitions could be extremely chaotic and violent, and there was no guarantee that the old political institutions would continuously and peacefully adapt to new conditions.

This model is a good starting point for a broader understanding of political decay more generally. Institutions are “stable, valued, recurring patterns of behavior,” as Huntington put it, the most important function of which is to facilitate collective action. Without some set of clear and relatively stable rules, human beings would have to renegotiate their interactions at every turn. Such rules are often culturally determined and vary across different societies and eras, but the capacity to create and adhere to them is genetically hard-wired into the human brain. A natural tendency to conformism helps give institutions inertia and is what has allowed human societies to achieve levels of social cooperation unmatched by any other animal species.

The very stability of institutions, however, is also the source of political decay. Institutions are created to meet the demands of specific circumstances, but then circumstances change and institutions fail to adapt. One reason is cognitive: people develop mental models of how the world works and tend to stick to them, even in the face of contradictory evidence. Another reason is group interest: institutions create favored classes of insiders who develop a stake in the status quo and resist pressures to reform.

In theory, democracy, and particularly the Madisonian version of democracy that was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, should mitigate the problem of such insider capture by preventing the emergence of a dominant faction or elite that can use its political power to tyrannize over the country. It does so by spreading power among a series of competing branches of government and allowing for competition among different interests across a large and diverse country.

But Madisonian democracy frequently fails to perform as advertised. Elite insiders typically have superior access to power and information, which they use to protect their interests. Ordinary voters will not get angry at a corrupt politician if they don’t know that money is being stolen in the first place. Cognitive rigidities or beliefs may also prevent social groups from mobilizing in their own interests. For example, in the United States, many working-class voters support candidates promising to lower taxes on the wealthy, despite the fact that such tax cuts will arguably deprive them of important government services.

Furthermore, different groups have different abilities to organize to defend their interests. Sugar producers and corn growers are geographically concentrated and focused on the prices of their products, unlike ordinary consumers or taxpayers, who are dispersed and for whom the prices of these commodities are only a small part of their budgets. Given institutional rules that often favor special interests (such as the fact that Florida and Iowa, where sugar and corn are grown, are electoral swing states), those groups develop an outsized influence over agricultural and trade policy. Similarly, middle-class groups are usually much more willing and able to defend their interests, such as the preservation of the home mortgage tax deduction, than are the poor. This makes such universal entitlements as Social Security or health insurance much easier to defend politically than programs targeting the poor only.

Finally, liberal democracy is almost universally associated with market economies, which tend to produce winners and losers and amplify what James Madison termed the “different and unequal faculties of acquiring property.” This type of economic inequality is not in itself a bad thing, insofar as it stimulates innovation and growth and occurs under conditions of equal access to the economic system. It becomes highly problematic, however, when the economic winners seek to convert their wealth into unequal political influence. They can do so by bribing a legislator or a bureaucrat, that is, on a transactional basis, or, what is more damaging, by changing the institutional rules to favor themselves -- for example, by closing off competition in markets they already dominate, tilting the playing field ever more steeply in their favor.

Political decay thus occurs when institutions fail to adapt to changing external circumstances, either out of intellectual rigidities or because of the power of incumbent elites to protect their positions and block change. Decay can afflict any type of political system, authoritarian or democratic. And while democratic political systems theoretically have self-correcting mechanisms that allow them to reform, they also open themselves up to decay by legitimating the activities of powerful interest groups that can block needed change.

This is precisely what has been happening in the United States in recent decades, as many of its political institutions have become increasingly dysfunctional. A combination of intellectual rigidity and the power of entrenched political actors is preventing those institutions from being reformed. And there is no guarantee that the situation will change much without a major shock to the political order.

A STATE OF COURTS AND PARTIES

Modern liberal democracies have three branches of government -- the executive, the judiciary, and the legislature -- corresponding to the three basic categories of political institutions: the state, the rule of law, and democracy. The executive is the branch that uses power to enforce rules and carry out policy; the judiciary and the legislature constrain power and direct it to public purposes. In its institutional priorities, the United States, with its long-standing tradition of distrust of government power, has always emphasized the role of the institutions of constraint -- the judiciary and the legislature -- over the state. The political scientist Stephen Skowronek has characterized American politics during the nineteenth century as a “state of courts and parties,” where government functions that in Europe would have been performed by an executive-branch bureaucracy were performed by judges and elected representatives instead. The creation of a modern, centralized, merit-based bureaucracy capable of exercising jurisdiction over the whole territory of the country began only in the 1880s, and the number of professional civil servants increased slowly up through the New Deal a half century later. These changes came far later and more hesitantly than in countries such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

The shift to a more modern administrative state was accompanied by an enormous growth in the size of government during the middle decades of the twentieth century. Overall levels of both taxes and government spending have not changed very much since the 1970s; despite the backlash against the welfare state that began with President Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, “big government” seems very difficult to dismantle. But the apparently irreversible increase in the scope of government in the twentieth century has masked a large decay in its quality. This is largely because the United States has returned in certain ways to being a “state of courts and parties,” that is, one in which the courts and the legislature have usurped many of the proper functions of the executive, making the operation of the government as a whole both incoherent and inefficient.

The story of the courts is one of the steadily increasing judicialization of functions that in other developed democracies are handled by administrative bureaucracies, leading to an explosion of costly litigation, slowness of decision-making, and highly inconsistent enforcement of laws. In the United States today, instead of being constraints on government, courts have become alternative instruments for the expansion of government.

There has been a parallel usurpation by Congress. Interest groups, having lost their ability to corrupt legislators directly through bribery, have found other means of capturing and controlling legislators. These interest groups exercise influence way out of proportion to their place in society, distort both taxes and spending, and raise overall deficit levels by their ability to manipulate the budget in their favor. They also undermine the quality of public administration through the multiple mandates they induce Congress to support.

Both phenomena -- the judicialization of administration and the spread of interest-group influence -- tend to undermine the trust that people have in government. Distrust of government then perpetuates and feeds on itself. Distrust of executive agencies leads to demands for more legal checks on administration, which reduces the quality and effectiveness of government. At the same time, demand for government services induces Congress to impose new mandates on the executive, which often prove difficult, if not impossible, to fulfill. Both processes lead to a reduction of bureaucratic autonomy, which in turn leads to rigid, rule-bound, uncreative, and incoherent government.

The result is a crisis of representation, in which ordinary citizens feel that their supposedly democratic government no longer truly reflects their interests and is under the control of a variety of shadowy elites. What is ironic and peculiar about this phenomenon is that this crisis of representation has occurred in large part because of reforms designed to make the system more democratic. In fact, these days there is too much law and too much democracy relative to American state capacity.

JUDGES GONE WILD

One of the great turning points in twentieth-century U.S. history was the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, which had upheld legal segregation. The Brown decision was the starting point for the civil rights movement, which succeeded in dismantling the formal barriers to racial equality and guaranteed the rights of African Americans and other minorities. The model of using the courts to enforce new social rules was then followed by many other social movements, from environmental protection and consumer safety to women’s rights and gay marriage.

So familiar is this heroic narrative to Americans that they are seldom aware of how peculiar an approach to social change it is. The primary mover in the Brown case was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a private voluntary association that filed a class-action suit against the Topeka, Kansas, Board of Education on behalf of a small group of parents and their children. The initiative had to come from private groups, of course, because both the state government and the U.S. Congress were blocked by pro-segregation forces. The NAACP continued to press the case on appeal all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was represented by the future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall. What was arguably one of the most important changes in American public policy came about not because Congress as representative of the American people voted for it but because private individuals litigated through the court system to change the rules. Later changes such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were the result of congressional action, but even in these cases, the enforcement of national law was left up to the initiative of private parties and carried out by courts.

There is virtually no other liberal democracy that proceeds in this fashion. All European countries have gone through similar changes in the legal status of racial and ethnic minorities, women, and gays in the second half of the twentieth century. But in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, the same result was achieved not using the courts but through a national justice ministry acting on behalf of a parliamentary majority. The legislative rule change was driven by public pressure from social groups and the media but was carried out by the government itself and not by private parties acting in conjunction with the justice system.

The origins of the U.S. approach lie in the historical sequence by which its three sets of institutions evolved. In countries such as France and Germany, law came first, followed by a modern state, and only later by democracy. In the United States, by contrast, a very deep tradition of English common law came first, followed by democracy, and only later by the development of a modern state. Although the last of these institutions was put into place during the Progressive Era and the New Deal, the American state has always remained weaker and less capable than its European or Asian counterparts. More important, American political culture since the founding has been built around distrust of executive authority.

This history has resulted in what the legal scholar Robert Kagan labels a system of “adversarial legalism.” While lawyers have played an outsized role in American public life since the beginning of the republic, their role expanded dramatically during the turbulent years of social change in the 1960s and 1970s. Congress passed more than two dozen major pieces of civil rights and environment legislation in this period, covering issues from product safety to toxic waste cleanup to private pension funds to occupational safety and health. This constituted a huge expansion of the regulatory state, one that businesses and conservatives are fond of complaining about today.

Yet what makes this system so unwieldy is not the level of regulation per se but the highly legalistic way in which it is pursued. Congress mandated the creation of an alphabet soup of new federal agencies, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, but it was not willing to cleanly delegate to these bodies the kind of rule-making authority and enforcement power that European or Japanese state institutions enjoy. What it did instead was turn over to the courts the responsibility for monitoring and enforcing the law. Congress deliberately encouraged litigation by expanding standing (that is, who has a right to sue) to an ever-wider circle of parties, many of which were only distantly affected by a particular rule.

The political scientist R. Shep Melnick, for example, has described the way that the federal courts rewrote Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, “turning a weak law focusing primarily on intentional discrimination into a bold mandate to compensate for past discrimination.” Instead of providing a federal bureaucracy with adequate enforcement power, the political scientist Sean Farhang explained, “the key move of Republicans in the Senate . . . was to substantially privatize the prosecutorial function. They made private lawsuits the dominant mode of Title VII enforcement, creating an engine that would, in the years to come, produce levels of private enforcement litigation beyond their imagining.” Across the board, private enforcement cases grew in number from less than 100 per year in the late 1960s to 10,000 in the 1980s and over 22,000 by the late 1990s.

Thus, conflicts that in Sweden or Japan would be solved through quiet consultations between interested parties in the bureaucracy are fought out through formal litigation in the U.S. court system. This has a number of unfortunate consequences for public administration, leading to a process characterized, in Farhang’s words, by “uncertainty, procedural complexity, redundancy, lack of finality, high transaction costs.” By keeping enforcement out of the bureaucracy, it also makes the system far less accountable.

The explosion of opportunities for litigation gave access, and therefore power, to many formerly excluded groups, beginning with African Americans. For this reason, litigation and the right to sue have been jealously guarded by many on the progressive left. But it also entailed large costs in terms of the quality of public policy. Kagan illustrates this with the case of the dredging of Oakland Harbor, in California. During the 1970s, the Port of Oakland initiated plans to dredge the harbor in anticipation of the new, larger classes of container ships that were then coming into service. The plan, however, had to be approved by a host of federal agencies, including the Army Corps of Engineers, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as their counterparts in the state of California. A succession of alternative plans for disposing of toxic materials dredged from the harbor were challenged in the courts, and each successive plan entailed prolonged delays and higher costs. The reaction of the Environmental Protection Agency to these lawsuits was to retreat into a defensive crouch and not take action. The final plan to proceed with the dredging was not forthcoming until 1994, at an ultimate cost that was many times the original estimates. A comparable expansion of the Port of Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, was accomplished in a fraction of the time.

Examples such as this can be found across the entire range of activities undertaken by the U.S. government. Many of the travails of the Forest Service can be attributed to the ways in which its judgments could be second-guessed through the court system. This effectively brought to a halt all logging on lands it and the Bureau of Land Management operated in the Pacific Northwest during the early 1990s, as a result of threats to the spotted owl, which was protected under the Endangered Species Act.

When used as an instrument of enforcement, the courts have morphed from constraints on government to mechanisms by which the scope of government has expanded enormously. For example, special-education programs for handicapped and disabled children have mushroomed in size and cost since the mid-1970s as a result of an expansive mandate legislated by Congress in 1974. This mandate was built, however, on earlier findings by federal district courts that special-needs children had rights, which are much harder than mere interests to trade off against other goods or to subject to cost-benefit criteria.

The solution to this problem is not necessarily the one advocated by many conservatives and libertarians, which is to simply eliminate regulation and close down bureaucracies. The ends that government is serving, such as the regulation of toxic waste or environmental protection or special education, are important ones that private markets will not pursue if left to their own devices. Conservatives often fail to see that it is the very distrust of government that leads the American system into a far less efficient court-based approach to regulation than that chosen in democracies with stronger executive branches.

But the attitude of progressives and liberals is equally problematic. They, too, have distrusted bureaucracies, such as the ones that produced segregated school systems in the South or the ones captured by big business, and they have been happy to inject unelected judges into the making of social policy when legislators have proved insufficiently supportive.

A decentralized, legalistic approach to administration dovetails with the other notable feature of the U.S. political system: its openness to the influence of interest groups. Such groups can get their way by suing the government directly. But they have another, even more powerful channel, one that controls significantly more resources: Congress.

LIBERTY AND PRIVILEGE

With the exception of some ambassadorships and top posts in government departments, U.S. political parties are no longer in the business of distributing government offices to loyal political supporters. But the trading of political influence for money has come in through the backdoor, in a form that is perfectly legal and much harder to eradicate. Criminalized bribery is narrowly defined in U.S. law as a transaction in which a politician and a private party explicitly agree on a specific quid pro quo. What is not covered by the law is what biologists call reciprocal altruism, or what an anthropologist might label a gift exchange. In a relationship of reciprocal altruism, one person confers a benefit on another with no explicit expectation that it will buy a return favor. Indeed, if one gives someone a gift and then immediately demands a gift in return, the recipient is likely to feel offended and refuse what is offered. In a gift exchange, the receiver incurs not a legal obligation to provide some specific good or service but rather a moral obligation to return the favor in some way later on. It is this sort of transaction that the U.S. lobbying industry is built around.

Kin selection and reciprocal altruism are two natural modes of human sociability. Modern states create strict rules and incentives to overcome the tendency to favor family and friends, including practices such as civil service examinations, merit qualifications, conflict-of-interest regulations, and antibribery and anticorruption laws. But the force of natural sociability is so strong that it keeps finding a way to penetrate the system.

Over the past half century, the American state has been “repatrimonialized,” in much the same way as the Chinese state in the Later Han dynasty, the Mamluk regime in Turkey just before its defeat by the Ottomans, and the French state under the ancien régime were. Rules blocking nepotism are still strong enough to prevent overt favoritism from being a common political feature in contemporary U.S. politics (although it is interesting to note how strong the urge to form political dynasties is, with all of the Kennedys, Bushes, Clintons, and the like). Politicians do not typically reward family members with jobs; what they do is engage in bad behavior on behalf of their families, taking money from interest groups and favors from lobbyists in order to make sure that their children are able to attend elite schools and colleges, for example.

Reciprocal altruism, meanwhile, is rampant in Washington and is the primary channel through which interest groups have succeeded in corrupting government. As the legal scholar Lawrence Lessig points out, interest groups are able to influence members of Congress legally simply by making donations and waiting for unspecified return favors. And sometimes, the legislator is the one initiating the gift exchange, favoring an interest group in the expectation that he will get some sort of benefit from it after leaving office.

The explosion of interest groups and lobbying in Washington has been astonishing, with the number of firms with registered lobbyists rising from 175 in 1971 to roughly 2,500 a decade later, and then to 13,700 lobbyists spending about $3.5 billion by 2009. Some scholars have argued that all this money and activity has not resulted in measurable changes in policy along the lines desired by the lobbyists, implausible as this may seem. But oftentimes, the impact of interest groups and lobbyists is not to stimulate new policies but to make existing legislation much worse than it would otherwise be. The legislative process in the United States has always been much more fragmented than in countries with parliamentary systems and disciplined parties. The welter of congressional committees with overlapping jurisdictions often leads to multiple and conflicting mandates for action. This decentralized legislative process produces incoherent laws and virtually invites involvement by interest groups, which, if not powerful enough to shape overall legislation, can at least protect their specific interests.

For example, the health-care bill pushed by the Obama administration in 2010 turned into something of a monstrosity during the legislative process as a result of all the concessions and side payments that had to be made to interest groups ranging from doctors to insurance companies to the pharmaceutical industry. In other cases, the impact of interest groups was to block legislation harmful to their interests. The simplest and most effective response to the 2008 financial crisis and the hugely unpopular taxpayer bailouts of large banks would have been a law that put a hard cap on the size of financial institutions or a law that dramatically raised capital requirements, which would have had much the same effect. If a cap on size existed, banks taking foolish risks could go bankrupt without triggering a systemic crisis and a government bailout. Like the Depression-era Glass-Steagall Act, such a law could have been written on a couple of sheets of paper. But this possibility was not seriously considered during the congressional deliberations on financial regulation.

What emerged instead was the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which, while better than no regulation at all, extended to hundreds of pages of legislation and mandated reams of further detailed rules that will impose huge costs on banks and consumers down the road. Rather than simply capping bank size, it created the Financial Stability Oversight Council, which was assigned the enormous task of assessing and managing institutions posing systemic risks, a move that in the end will still not solve the problem of banks being “too big to fail.” Although no one will ever find a smoking gun linking banks’ campaign contributions to the votes of specific members of Congress, it defies belief that the banking industry’s legions of lobbyists did not have a major impact in preventing the simpler solution of simply breaking up the big banks or subjecting them to stringent capital requirements.

Ordinary Americans express widespread disdain for the impact of interest groups and money on Congress. The perception that the democratic process has been corrupted or hijacked is not an exclusive concern of either end of the political spectrum; both Tea Party Republicans and liberal Democrats believe that interest groups are exercising undue political influence and feathering their own nests. As a result, polls show that trust in Congress has fallen to historically low levels, barely above single digits -- and the respondents have a point. Of the old elites in France prior to the Revolution, Alexis de Tocqueville said that they mistook privilege for liberty, that is, they sought protection from state power that applied to them alone and not generally to all citizens. In the contemporary United States, elites speak the language of liberty but are perfectly happy to settle for privilege.

WHAT MADISON GOT WRONG

The economist Mancur Olson made one of the most famous arguments about the malign effects of interest-group politics on economic growth and, ultimately, democracy in his 1982 book The Rise and Decline of Nations. Looking particularly at the long-term economic decline of the United Kingdom throughout the twentieth century, he argued that in times of peace and stability, democracies tended to accumulate ever-increasing numbers of interest groups. Instead of pursuing wealth-creating economic activities, these groups used the political system to extract benefits or rents for themselves. These rents were collectively unproductive and costly to the public as a whole. But the general public had a collective-action problem and could not organize as effectively as, for example, the banking industry or corn producers to protect their interests. The result was the steady diversion of energy to rent-seeking activities over time, a process that could be halted only by a large shock such as a war or a revolution.

This highly negative narrative about interest groups stands in sharp contrast to a much more positive one about the benefits of civil society, or voluntary associations, to the health of democracy. Tocqueville noted in Democracy in America that Americans had a strong propensity to organize private associations, which he argued were schools for democracy because they taught private individuals the skills of coming together for public purposes. Individuals by themselves were weak; only by coming together for common purposes could they, among other things, resist tyrannical government. This perspective was carried forward in the late twentieth century by scholars such as Robert Putnam, who argued that this very propensity to organize -- “social capital” -- was both good for democracy and endangered.

Madison himself had a relatively benign view of interest groups. Even if one did not approve of the ends that a particular group was seeking, he argued, the diversity of groups over a large country would be sufficient to prevent domination by any one of them. As the political scientist Theodore Lowi has noted, “pluralist” political theory in the mid-twentieth century concurred with Madison: the cacophony of interest groups would collectively interact to produce a public interest, just as competition in a free market would provide public benefit through individuals’ following their narrow self-interests. There were no grounds for the government to regulate this process, since there was no higher authority that could define a public interest standing above the narrow concerns of interest groups. The Supreme Court in its Buckley v. Valeo and Citizens United decisions, which struck down certain limits on campaign spending by groups, was in effect affirming the benign interpretation of what Lowi has labeled “interest group liberalism.”

How can these diametrically opposed narratives be reconciled? The most obvious way is to try to distinguish a “good” civil society organization from a “bad” interest group. The former could be said to be driven by passions, the latter by interests. A civil society organization might be a nonprofit such as a church group seeking to build houses for the poor or else a lobbying organization promoting a public policy it believed to be in the public interest, such as the protection of coastal habitats. An interest group might be a lobbying firm representing the tobacco industry or large banks, whose objective was to maximize the profits of the companies supporting it.

Unfortunately, this distinction does not hold up to theoretical scrutiny. Just because a group proclaims that it is acting in the public interest does not mean that it is actually doing so. For example, a medical advocacy group that wanted more dollars allocated to combating a particular disease might actually distort public priorities by diverting funds from more widespread and damaging diseases, simply because it is better at public relations. And because an interest group is self-interested doesn’t mean that its claims are illegitimate or that it does not have a right to be represented within the political system. If a poorly-thought-out regulation would seriously damage the interests of an industry and its workers, the relevant interest group has a right to make that known to Congress. In fact, such lobbyists are often some of the most important sources of information about the consequences of government action.

The most salient argument against interest-group pluralism has to do with distorted representation. In his 1960 book The Semisovereign People, E. E. Schattschneider argued that the actual practice of democracy in the United States had nothing to do with its popular image as a government “of the people, by the people, for the people.” He noted that political outcomes seldom correspond with popular preferences, that there is a very low level of participation and political awareness, and that real decisions are taken by much smaller groups of organized interests. A similar argument is buried in Olson’s framework, since Olson notes that not all groups are equally capable of organizing for collective action. The interest groups that contend for the attention of Congress represent not the whole American people but the best-organized and (what often amounts to the same thing) most richly endowed parts of American society. This tends to work against the interests of the unorganized, who are often poor, poorly educated, or otherwise marginalized.

The political scientist Morris Fiorina has provided substantial evidence that what he labels the American “political class” is far more polarized than the American people themselves. But the majorities supporting middle-of-the-road positions do not feel very passionately about them, and they are largely unorganized. This means that politics is defined by well-organized activists, whether in the parties and Congress, the media, or in lobbying and interest groups. The sum of these activist groups does not yield a compromise position; it leads instead to polarization and deadlocked politics.

There is a further problem with the pluralistic view, which sees the public interest as nothing more than the aggregation of individual private interests: it undermines the possibility of deliberation and the process by which individual preferences are shaped by dialogue and communication. Both classical Athenian democracy and the New England town hall meetings celebrated by Tocqueville were cases in which citizens spoke directly to one another about the common interests of their communities. It is easy to idealize these instances of small-scale democracy, or to minimize the real differences that exist in large societies. But as any organizer of focus groups will tell you, people’s views on highly emotional subjects, from immigration to abortion to drugs, will change just 30 minutes into a face-to-face discussion with people of differing views, provided that they are all given the same information and ground rules that enforce civility. One of the problems of pluralism, then, is the assumption that interests are fixed and that the role of the legislator is simply to act as a transmission belt for them, rather than having his own views that can be shaped by deliberation.

THE RISE OF VETOCRACY

The U.S. Constitution protects individual liberties through a complex system of checks and balances that were deliberately designed by the founders to constrain the power of the state. American government arose in the context of a revolution against British monarchical authority and drew on even deeper wellsprings of resistance to the king during the English Civil War. Intense distrust of government and a reliance on the spontaneous activities of dispersed individuals have been hallmarks of American politics ever since.

As Huntington pointed out, in the U.S. constitutional system, powers are not so much functionally divided as replicated across the branches, leading to periodic usurpations of one branch by another and conflicts over which branch should predominate. Federalism often does not cleanly delegate specific powers to the appropriate level of government; rather, it duplicates them at multiple levels, giving federal, state, and local authorities jurisdiction over, for example, toxic waste disposal. Under such a system of redundant and non-hierarchical authority, different parts of the government are easily able to block one another. In conjunction with the general judicialization of politics and the widespread influence of interest groups, the result is an unbalanced form of government that undermines the prospects of necessary collective action -- something that might more appropriately be called “vetocracy.”

The two dominant American political parties have become more ideologically polarized than at any time since the late nineteenth century. There has been a partisan geographic sorting, with virtually the entire South moving from Democratic to Republican and Republicans becoming virtually extinct in the Northeast. Since the breakdown of the New Deal coalition and the end of the Democrats’ hegemony in Congress in the 1980s, the two parties have become more evenly balanced and have repeatedly exchanged control over the presidency and Congress. This higher degree of partisan competition, in turn, along with liberalized campaign-finance guidelines, has fueled an arms race between the parties for funding and has undermined personal comity between them. The parties have also increased their homogeneity through their control, in most states, over redistricting, which allows them to gerrymander voting districts to increase their chances of reelection. The spread of primaries, meanwhile, has put the choice of party candidates into the hands of the relatively small number of activists who turn out for these elections.

Polarization is not the end of the story, however. Democratic political systems are not supposed to end conflict; rather, they are meant to peacefully resolve and mitigate it through agreed-on rules. A good political system is one that encourages the emergence of political outcomes representing the interests of as large a part of the population as possible. But when polarization confronts the United States’ Madisonian check-and-balance political system, the result is particularly devastating.

Democracies must balance the need to allow full opportunities for political participation for all, on the one hand, and the need to get things done, on the other. Ideally, democratic decisions would be taken by consensus, with every member of the community consenting. This is what typically happens in families, and how band- and tribal-level societies often make decisions. The efficiency of consensual decision-making, however, deteriorates rapidly as groups become larger and more diverse, and so for most groups, decisions are made not by consensus but with the consent of some subset of the population. The smaller the percentage of the group necessary to take a decision, the more easily and efficiently it can be made, but at the expense of long-run buy-in.

Even systems of majority rule deviate from an ideal democratic procedure, since they can disenfranchise nearly half the population. Indeed, under a plurality, or “first past the post,” electoral system, decisions can be taken for the whole community by a minority of voters. Systems such as these are adopted not on the basis of any deep principle of justice but rather as an expedient that allows decisions of some sort to be made. Democracies also create various other mechanisms, such as cloture rules (enabling the cutting off of debate), rules restricting the ability of legislators to offer amendments, and so-called reversionary rules, which allow for action in the event that a legislature can’t come to agreement.

The delegation of powers to different political actors enables them to block action by the whole body. The U.S. political system has far more of these checks and balances, or what political scientists call “veto points,” than other contemporary democracies, raising the costs of collective action and in some cases make it impossible altogether. In earlier periods of U.S. history, when one party or another was dominant, this system served to moderate the will of the majority and force it to pay greater attention to minorities than it otherwise might have. But in the more evenly balanced, highly competitive party system that has arisen since the 1980s, it has become a formula for gridlock.

By contrast, the so-called Westminster system, which evolved in England in the years following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, is one of the most decisive in the democratic world because, in its pure form, it has very few veto points. British citizens have one large, formal check on government, their ability to periodically elect Parliament. (The tradition of free media in the United Kingdom is another important informal check.) In all other respects, however, the system concentrates, rather than diffuses, power. The pure Westminster system has only a single, all-powerful legislative chamber -- no separate presidency, no powerful upper house, no written constitution and therefore no judicial review, and no federalism or constitutionally mandated devolution of powers to localities. It has a plurality voting system that, along with strong party discipline, tends to produce a two-party system and strong parliamentary majorities. The British equivalent of the cloture rule requires only a simple majority of the members of Parliament to be present to call the question; American-style filibustering is not allowed. The parliamentary majority chooses a government with strong executive powers, and when it makes a legislative decision, it generally cannot be stymied by courts, states, municipalities, or other bodies. This is why the British system is often described as a “democratic dictatorship.”

For all its concentrated powers, the Westminster system nonetheless remains fundamentally democratic, because if voters don’t like the government it produces, they can vote it out of office. In fact, with a vote of no confidence, they can do so immediately, without waiting for the end of a presidential term. This means that governments are more sensitive to perceptions of their general performance than to the needs of particular interest groups or lobbies.

The Westminster system produces stronger governments than those in the United States, as can be seen by comparing their budget processes. In the United Kingdom, national budgets are drawn up by professional civil servants acting under instructions from the cabinet and the prime minister. The budget is then presented by the chancellor of the exchequer to the House of Commons, which votes to approve it in a single up-or-down vote, usually within a week or two.

In the United States, by contrast, Congress has primary authority over the budget. Presidents make initial proposals, but these are largely aspirational documents that do not determine what eventually emerges. The executive branch’s Office of Management and Budget has no formal powers over the budget, acting as simply one more lobbying organization supporting the president’s preferences. The budget works its way through a complex set of committees over a period of months, and what finally emerges for ratification by the two houses of Congress is the product of innumerable deals struck with individual members to secure their support -- since with no party discipline, the congressional leadership cannot compel members to support its preferences.

The openness and never-ending character of the U.S. budget process gives lobbyists and interest groups multiple points at which to exercise influence. In most European parliamentary systems, it would make no sense for an interest group to lobby an individual member of parliament, since the rules of party discipline would give that legislator little or no influence over the party leadership’s position. In the United States, by contrast, an influential committee chairmanship confers enormous powers to modify legislation and therefore becomes the target of enormous lobbying activity.

Of the challenges facing developed democracies, one of the most important is the problem of the unsustainability of their existing welfare-state commitments. The existing social contracts underlying contemporary welfare states were negotiated several generations ago, when birthrates were higher, lifespans were shorter, and economic growth rates were robust. The availability of finance has allowed all modern democracies to keep pushing this problem into the future, but at some point, the underlying demographic reality will set in.

These problems are not insuperable. The debt-to-GDP ratios of both the United Kingdom and the United States coming out of World War II were higher than they are today. Sweden, Finland, and other Scandinavian countries found their large welfare states in crisis during the 1990s and were able to make adjustments to their tax and spending levels. Australia succeeded in eliminating almost all its external debt, even prior to the huge resource boom of the early years of this century. But dealing with these problems requires a healthy, well-functioning political system, which the United States does not currently have. Congress has abdicated one of its most basic responsibilities, having failed to follow its own rules for the orderly passing of budgets several years in a row now.

The classic Westminster system no longer exists anywhere in the world, including the United Kingdom itself, as that country has gradually adopted more checks and balances. Nonetheless, the United Kingdom still has far fewer veto points than does the United States, as do most parliamentary systems in Europe and Asia. (Certain Latin American countries, having copied the U.S. presidential system in the nineteenth century, have similar problems with gridlock and politicized administration.)

Budgeting is not the only aspect of government that is handled differently in the United States. In parliamentary systems, a great deal of legislation is formulated by the executive branch with heavy technocratic input from the permanent civil service. Ministries are accountable to parliament, and hence ultimately to voters, through the ministers who head them, but this type of hierarchical system can take a longer-term strategic view and produce much more coherent legislation.

Such a system is utterly foreign to the political culture in Washington, where Congress jealously guards its right to legislate -- even though the often incoherent product is what helps produce a large, sprawling, and less accountable government. Congress’ multiple committees frequently produce duplicate and overlapping programs or create several agencies with similar purposes. The Pentagon, for example, operates under nearly 500 mandates to report annually to Congress on various issues. These never expire, and executing them consumes huge amounts of time and energy. Congress has created about 50 separate programs for worker retraining and 82 separate projects to improve teacher quality.

Financial-sector regulation is split between the Federal Reserve, the Treasury Department, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and a host of state attorneys general who have decided to take on the banking sector. The federal agencies are overseen by different congressional committees, which are loath to give up their turf to a more coherent and unified regulator. This system was easy to game so as to bring about the deregulation of the financial sector in the late 1990s; re-regulating it after the recent financial crisis has proved much more difficult.

CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION

Vetocracy is only half the story of the U.S. political system. In other respects, Congress delegates huge powers to the executive branch, which allow the latter to operate rapidly and sometimes with a very low degree of accountability. Such areas of delegation include the Federal Reserve, the intelligence agencies, the military, and a host of quasi-independent commissions and regulatory agencies that together constitute the huge administrative state that emerged during the Progressive Era and the New Deal.

While many American libertarians and conservatives would like to abolish these agencies altogether, it is hard to see how it would be possible to govern properly under modern circumstances without them. The United States today has a huge, complex national economy, situated in a globalized world economy that moves with extraordinary speed. During the acute phase of the financial crisis that unfolded after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department had to make massive decisions overnight, decisions that involved flooding markets with trillions of dollars of liquidity, propping up individual banks, and imposing new regulations. The severity of the crisis led Congress to appropriate $700 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program largely on the say-so of the Bush administration. There has been a lot of second-guessing of individual decisions made during this period, but the idea that such a crisis could have been managed by any other branch of government is ludicrous. The same applies to national security issues, where the president is in effect tasked with making decisions on how to respond to nuclear and terrorist threats that potentially affect the lives of millions of Americans. It is for this reason that Alexander Hamilton, in The Federalist Papers, no. 70, spoke of the need for “energy in the executive.”

There is intense populist distrust of elite institutions in the United States, together with calls to abolish them (as in the case of the Federal Reserve) or make them more transparent. Ironically, however, polls show the highest degree of approval for precisely those institutions, such as the military or NASA, that are the least subject to immediate democratic oversight. Part of the reason they are admired is that they can actually get things done. By contrast, the most democratic institution, the House of Representatives, receives disastrously low levels of approval, and Congress more broadly is regarded (not inaccurately) as a talking shop where partisan games prevent almost anything useful from happening.

In full perspective, therefore, the U.S. political system presents a complex picture in which checks and balances excessively constrain decision-making on the part of majorities, but in which there are also many instances of potentially dangerous delegations of authority to poorly accountable institutions. One major problem is that these delegations are seldom made cleanly. Congress frequently fails in its duty to provide clear legislative guidance on how a particular agency is to perform its task, leaving it up to the agency itself to write its own mandate. In doing so, Congress hopes that if things don’t work out, the courts will step in to correct the abuses. Excessive delegation and vetocracy thus become intertwined.

In a parliamentary system, the majority party or coalition controls the government directly; members of parliament become ministers who have the authority to change the rules of the bureaucracies they control. Parliamentary systems can be blocked if parties are excessively fragmented and coalitions unstable, as has been the case frequently in Italy. But once a parliamentary majority has been established, there is a relatively straight-forward delegation of authority to an executive agency.

Such delegations are harder to achieve, however, in a presidential system. The obvious solution to a legislature’s inability to act is to transfer more authority to the separately elected executive. Latin American countries with presidential systems have been notorious for gridlock and ineffective legislatures and have often cut through the maze by granting presidents emergency powers -- which, in turn, has often led to other kinds of abuses. Under conditions of divided government, when the party controlling one or both houses of Congress is different from the one controlling the presidency, strengthening the executive at the expense of Congress becomes a matter of partisan politics. Delegating more authority to President Barack Obama is the last thing that House Republicans want to do today.

In many respects, the American system of checks and balances compares unfavorably with parliamentary systems when it comes to the ability to balance the need for strong state action with law and accountability. Parliamentary systems tend not to judicialize administration to nearly the same extent; they have proliferated government agencies less, they write more coherent legislation, and they are less subject to interest-group influence. Germany, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries, in particular, have been able to sustain higher levels of trust in government, which makes public administration less adversarial, more consensual, and better able to adapt to changing conditions of globalization. (High-trust arrangements, however, tend to work best in relatively small, homogeneous societies, and those in these countries have been showing signs of strain as their societies have become more diverse as a result of immigration and cultural change.)

The picture looks a bit different for the EU as a whole. Recent decades have seen a large increase in the number and sophistication of lobbying groups in Europe, for example. These days, corporations, trade associations, and environmental, consumer, and labor rights groups all operate at both national and EU-wide levels. And with the shift of policymaking away from national capitals to Brussels, the European system as a whole is beginning to resemble that of the United States in depressing ways. Europe’s individual parliamentary systems may allow for fewer veto points than the U.S. system of checks and balances, but with the addition of a large European layer, many more veto points have been added. This means that European interest groups are increasingly able to venue shop: if they cannot get favorable treatment at the national level, they can go to Brussels, or vice versa. The growth of the EU has also Americanized Europe with respect to the role of the judiciary. Although European judges remain more reluctant than their U.S. counterparts to insert themselves into political matters, the new structure of European jurisprudence, with its multiple and overlapping levels, has increased, rather than decreased, the number of judicial vetoes in the system.

NO WAY OUT

The U.S. political system has decayed over time because its traditional system of checks and balances has deepened and become increasingly rigid. In an environment of sharp political polarization, this decentralized system is less and less able to represent majority interests and gives excessive representation to the views of interest groups and activist organizations that collectively do not add up to a sovereign American people.

This is not the first time that the U.S. political system has been polarized and indecisive. In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, it could not make up its mind about the extension of slavery to the territories, and in the later decades of the century, it couldn’t decide if the country was a fundamentally agrarian society or an industrial one. The Madisonian system of checks and balances and the clientelistic, party-driven political system that emerged in the nineteenth century were adequate for governing an isolated, largely agrarian country. They could not, however, resolve the acute political crisis produced by the question of the extension of slavery, nor deal with a continental-scale economy increasingly knit together by new transportation and communications technologies.

Today, once again, the United States is trapped by its political institutions. Because Americans distrust government, they are generally unwilling to delegate to it the authority to make decisions, as happens in other democracies. Instead, Congress mandates complex rules that reduce the government’s autonomy and cause decision-making to be slow and expensive. The government then doesn’t perform well, which confirms people’s lack of trust in it. Under these circumstances, they are reluctant to pay higher taxes, which they feel the government will simply waste. But without appropriate -resources, the government can’t function properly, again creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Two obstacles stand in the way of reversing the trend toward decay. The first is a matter of politics. Many political actors in the United States recognize that the system isn’t working well but nonetheless have strong interests in keeping things as they are. Neither political party has an incentive to cut itself off from access to interest-group money, and the interest groups don’t want a system in which money won’t buy influence. As happened in the 1880s, a reform coalition has to emerge that unites groups without a stake in the current system. But achieving collective action among such out-groups is very difficult; they need leadership and a clear agenda, neither of which is currently present.

The second problem is a matter of ideas. The traditional American solution to perceived governmental dysfunction has been to try to expand democratic participation and transparency. This happened at a national level in the 1970s, for example, as reformers pushed for more open primaries, greater citizen access to the courts, and round-the-clock media coverage of Congress, even as states such as California expanded their use of ballot initiatives to get around unresponsive government. But as the political scientist Bruce Cain has pointed out, most citizens have neither the time, nor the background, nor the inclination to grapple with complex public policy issues; expanding participation has simply paved the way for well-organized groups of activists to gain more power. The obvious solution to this problem would be to roll back some of the would-be democratizing reforms, but no one dares suggest that what the country needs is a bit less participation and transparency.

The depressing bottom line is that given how self-reinforcing the country’s political malaise is, and how unlikely the prospects for constructive incremental reform are, the decay of American politics will probably continue until some external shock comes along to catalyze a true reform coalition and galvanize it into action.

Professor of Law at Suffolk University Law School, Boston

America in decay: Is Fukuyama right?

by alasdairroberts on August 25, 2014

One of the odd consequences of the global financial crisis — an instance of massive market failure — has been a boom in literature about the defects of contemporary democracy. I’ve recently written reviews of several books in this genre. In the new issue of Foreign Affairs, the distinguished political scientist Francis Fukuyama joins in the fray. America, says Fukuyama, is in the process of “political decay.” Certainly, this is not the best of times for American democracy. But there are five reasons why we should take Fukuyama’s assessment with a grain of salt.

First, a nutshell of Fukuyama’s argument. The U.S. political system is in decay. Its major political institutions are “increasingly dysfunctional,” and the effectiveness of federal agencies in performing critical functions is in long-term decline. There are two major reasons for this. First, Congress has too much influence over the executive branch. Bending to the influence of interest groups, Congress imposes multiple mandates and restrictions on the federal bureaucracy, impeding its ability to get work done. Congress has also been undermined because of its inability to control the fallout from political polarization. (Fukuyama follows the argument by Mann and Ornstein here.) At the same time, courts have extended their influence over the executive branch, with similarly malign effects. The current woes of the federal government have their roots in choices about constitutional design made long ago. The “traditional system of checks and balances” is ill-suited to the complexities of modern governance. But the probability of improvement is low: there is no well-organized coalition pressing for reform, and there are few ideas on how the system might be made better.

Now, here are five major limitations of this argument:

1. Confusing American government with the federal government alone

Fukuyama’s article provides us with a dire assessment of the state of American politics — that is, the whole of it. Here are some quotes that illustrate the breadth of Fukuyama’s indictment:

[W]hile democratic political systems theoretically have self-correcting mechanisms that allow them to reform, they also open themselves up to decay by legitimating the activities of powerful interest groups that can block needed change. This is precisely what has been happening in the United States in recent decades, as many of its political institutions have become increasingly dysfunctional. (p. 10)

In fact, these days there is too much law and too much democracy relative to American state capacity. (p. 12)

Over the past half century, the American state has been “repatrimonialized.” (p. 15)

In full perspective, therefore, the U.S. political system presents a complex picture in which checks and balances excessively constraint decisionmaking on the part of majorities, but in which there are also many instances of potentially dangerous delegations of authority to poorly accountable institutions. (p. 24)

The U.S. political system has decayed over time because its traditional system of checks and balances has deepened and become increasingly rigid . . . This is not the first time that the U.S. political system has been polarized and indecisive . . . Today, once again, the United States is trapped by its political institutions. . . . [T]he decay of American politics will probably continue until some external shock comes along. (pp. 25-26)

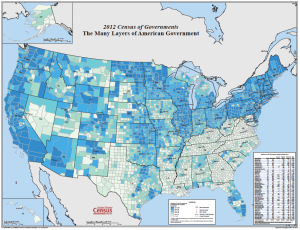

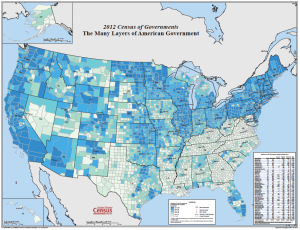

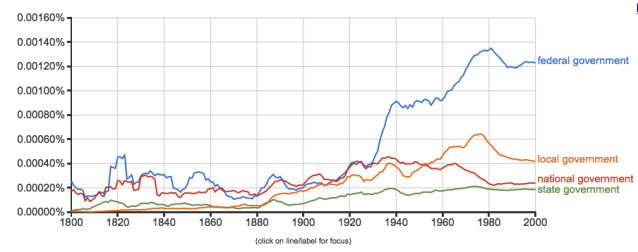

All of these criticisms of “the American state” and “the U.S. political system” and “American politics” might be right, but they are not substantiated by this article, which focuses primarily on federal politics and institutions. There are also fifty state governments, five territorial governments, three thousand county governments, sixteen thousand township governments, twenty thousand municipal governments, and fifty thousand district governments. (The Census Bureau provides a helpful map.) Fukuyama says little about how all of these institutions are working. Perhaps it could be argued that state and local government is dysfunctional too, but Fukuyama does not make that claim. (For example, you could argue that there are simply too many units of government.) Alternatively, it might be argued that federal politics is so important that a damning judgment on that aspect alone is enough to discredit the whole “U.S. political system.” Probably, that is Fukuyama’s position. But it ought to be stated explicitly — because it involves an assumption about the proper role of the federal government in American life, which many Americans might disagree with. (See #5, below. This, incidentally, is an error that is made by many authors who lament the current state of American democracy.)

All of these criticisms of “the American state” and “the U.S. political system” and “American politics” might be right, but they are not substantiated by this article, which focuses primarily on federal politics and institutions. There are also fifty state governments, five territorial governments, three thousand county governments, sixteen thousand township governments, twenty thousand municipal governments, and fifty thousand district governments. (The Census Bureau provides a helpful map.) Fukuyama says little about how all of these institutions are working. Perhaps it could be argued that state and local government is dysfunctional too, but Fukuyama does not make that claim. (For example, you could argue that there are simply too many units of government.) Alternatively, it might be argued that federal politics is so important that a damning judgment on that aspect alone is enough to discredit the whole “U.S. political system.” Probably, that is Fukuyama’s position. But it ought to be stated explicitly — because it involves an assumption about the proper role of the federal government in American life, which many Americans might disagree with. (See #5, below. This, incidentally, is an error that is made by many authors who lament the current state of American democracy.)

2. Exaggerating the lack of exit routes

Fukuyama — or at least the editors at Foreign Affairs — tell us that there is “no way out” of the country’s current predicament (p. 25). One reason why is the inability to generate clever ways of making current institutions work better. As Fukuyama says:

The second problem is a matter of ideas. The traditional American solution to perceived governmental dysfunction has been to try to expand democratic participation and transparency. This happened at a national level in the 1970s, for example, as reformers pushed for more open primaries, greater citizen access to the courts, and round-the-clock media coverage of Congress (p. 26)

This is a misreading of history. Or to put it more precisely, this is a reading of history that puts undue weight on the experience of the 1970s, when the thrust of institutional change was toward participation and transparency. In the longer run, however, Americans have experimented with many responses to governmental dysfunction. For example:

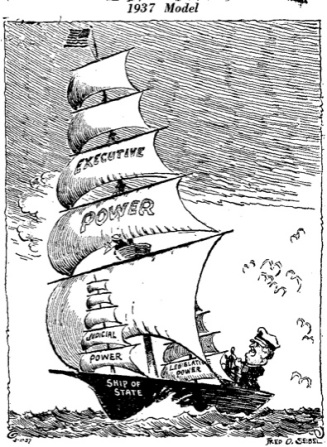

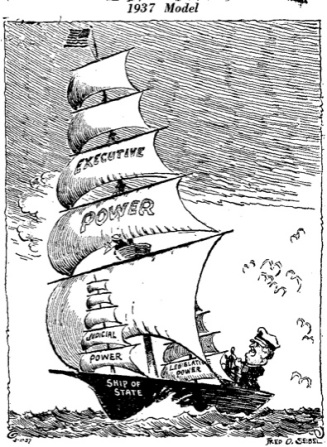

In the 1930s, the “crisis of democracy” was dealt with by bolstering presidential power over the executive branch. “The President’s administrative equipment is is far less developed than his responsibilities,” said the 1937 report of the President’s Committee on Administrative Management, “a major task before the American Government is to remedy this dangerous situation.” This led to creation of the Executive Office of the President, the reorganization of the Bureau of the Budget, and the creation of a National Resources Planning Board, among other things. (The cartoon at right, from the Richmond Times Dispatch of March 11, 1937, shows what some critics thought of the reforms at the time.) And the United States has bolstered executive power at other critical moments as well — such as in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, and in the early phase of the financial crisis in Fall 2008.

In the 1930s, the “crisis of democracy” was dealt with by bolstering presidential power over the executive branch. “The President’s administrative equipment is is far less developed than his responsibilities,” said the 1937 report of the President’s Committee on Administrative Management, “a major task before the American Government is to remedy this dangerous situation.” This led to creation of the Executive Office of the President, the reorganization of the Bureau of the Budget, and the creation of a National Resources Planning Board, among other things. (The cartoon at right, from the Richmond Times Dispatch of March 11, 1937, shows what some critics thought of the reforms at the time.) And the United States has bolstered executive power at other critical moments as well — such as in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, and in the early phase of the financial crisis in Fall 2008.- There have also been other large-scale reorganizations that have been designed to address major threats to American welfare. We should not forget the massive reorganization of defense and intelligence agencies under the National Security Act of 1947, and subsequent renovation of the defense establishment by the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986, as well as the massive reorganization of domestic security functions by the Homeland Security Act of 2002. There were flaws with all of these reorganizations, of course. But they do bolster the position that American politicians have responded to governance crises through techniques other than “participation and transparency.”

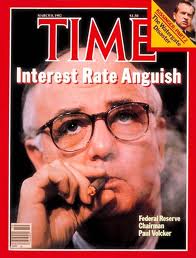

More evidence on this point: Sometimes the “crisis of democracy” has been dealt with by delegating more authority to technocrats who are buffered from political control, either by Congress or the President. For example, one response to the economic malaise of the 1970s was bolstering the independence of the Federal Reserve. This was about expert, rather than executive, power. Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987, was given the freedom to make deeply unpopular decisions about interest rates. We tend to forget how much the role of the Federal Reserve has shifted in the last forty years. In 1967, John Kenneth Galbraith said that the Federal Reserve ought to be regarded as “a minor instrumentality of the state . . . standing in importance between the Bureau of Printing and Engraving and the Interstate Commerce Commission.” By 2000, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan had “rock star status.”

More evidence on this point: Sometimes the “crisis of democracy” has been dealt with by delegating more authority to technocrats who are buffered from political control, either by Congress or the President. For example, one response to the economic malaise of the 1970s was bolstering the independence of the Federal Reserve. This was about expert, rather than executive, power. Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987, was given the freedom to make deeply unpopular decisions about interest rates. We tend to forget how much the role of the Federal Reserve has shifted in the last forty years. In 1967, John Kenneth Galbraith said that the Federal Reserve ought to be regarded as “a minor instrumentality of the state . . . standing in importance between the Bureau of Printing and Engraving and the Interstate Commerce Commission.” By 2000, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan had “rock star status.”- In the 1990s and early 2000s, another response to the crisis of democracy was privatization of key functions. This was a more radical way of taking key functions out of the control of democratically elected politicians. One example might be ICANN, the body that helps to regulate the internet, which is now set up as a non-profit corporation under California law. And of course there are a vast number of people who perform federal functions but work for contractors — which is another way of accommodating perceived dysfunction in federal laws governing the bureaucracy.